(Editor’s note: This reflection on farm policy is one of several policy pieces written by Agri-Pulse Editor Sara Wyant this year.)

I can still remember the speech I gave several years ago about the end of direct payments in the 2014 farm bill. Policymakers had been moving in this direction since before 2008 and it was clear that sending about $5 billion annually into farm country — regardless of what was planted — was no longer politically palpable.

First instituted in 1996 as a transition payment, the direct payment program provided a fixed payment to farmers regardless of on-farm decisions or on-farm prices. It was initially designed to run until 2002, but like many programs that become popular, ran for more than 15 years.

Little wonder then that the end of direct payments was a hard reality for many farmers. One came up to me after I ended my speech and told me quietly, “I don’t know how I’m going to make it without direct payments.”

It was a gut-wrenching moment. I reminded myself that I didn’t make the news, I just reported the news. But still, my heart went out to this man and his family. The only encouraging comment I could think of was that he was at a land grant university conference and there were people willing and able to help him move ahead.

Fast forward to 2018-19 and farmers, in general, were moving on with market-oriented farm bills which are decoupled from planting decisions. They were focused on what they would be able to get from both the market and the government in the coming years.

But as they look ahead to 2020, it’s a difficult “crystal ball” to decipher, both for farmers and their lenders, as well as those who will be attending policy sessions, trying to decide what they should recommend next to their respective farm and commodity organizations.

For now, there are more questions than answers about what lies ahead. Will there still be a trade war with China? Will there be new tariff tussles with Brazil, France or other countries that impact markets? And will the Trump administration provide more Market Facilitation Program (MFP) payments?

In the background, I imagine there will be a farmer somewhere saying, “I don’t know how I’m going to make it without my MFP payments.”

To be sure, the MFP is unlike the direct payment program in several ways. At the University of Illinois, Jonathan Coppess, Gary Schnitkey and Krista Swanson recently penned a paper titled, “The Market Facilitation Program: A New Direction in Public Agricultural Policy,” which explores many of the differences. As they point out:

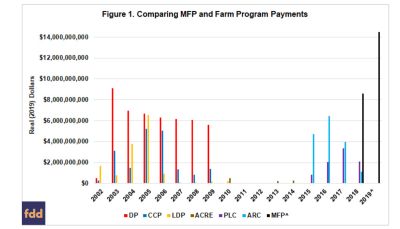

The MFP payments could be much bigger than anything witnessed under the farm bills with direct payments. “If all three tranches of MFP 2019 are made — and there is little reason to doubt that they will — the total spending for both the 2018 and 2019 versions could exceed $24 billion,” they note. Their chart (below) clearly shows the differences in spending.

MFP payments were not authorized by Congress as part of a farm or appropriations bill. “MFP was created because President Trump directed the Secretary of Agriculture to provide assistance to farmers due to the tariff conflict and, specifically, the retaliatory tariffs from key agricultural export markets such as China. USDA developed the specific aspects of MFP in a truncated rulemaking process,” the authors noted.

Interested in more future direction of farm programs coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

MFP also marks a reversal from decoupling of payments from production, they argue, steering farm policy away from decoupling efforts by Congress over the last 22 years.

“MFP has fully recoupled payments to production decisions,” the University of Illinois authors suggest. “The 2018 version was based on actual production records of the crops for which payments were made, although the program was announced after planting decisions had been made. The 2019 version required that the farmer plant a crop to receive any payment, including eventually accepting the planting of a cover crop on prevent planting acres in return for the minimum $15 per acre payment.”

The 2019 version of MFP made payments using a single county-wide payment rate, calculated using commodity rates and production histories of each county. As our Agri-Pulse team reported in a county-by-county map earlier this year, the highest payments are concentrated in southern counties with cotton production. (See map here.)

Most farmers tell me that the MFP payment didn’t make them whole, but the payments were extremely helpful in bridging some of the income gaps they faced this year. Going forward, it will be interesting to see how many farmers would like to see MFP continue, direct payments return or some other types of policy options.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com