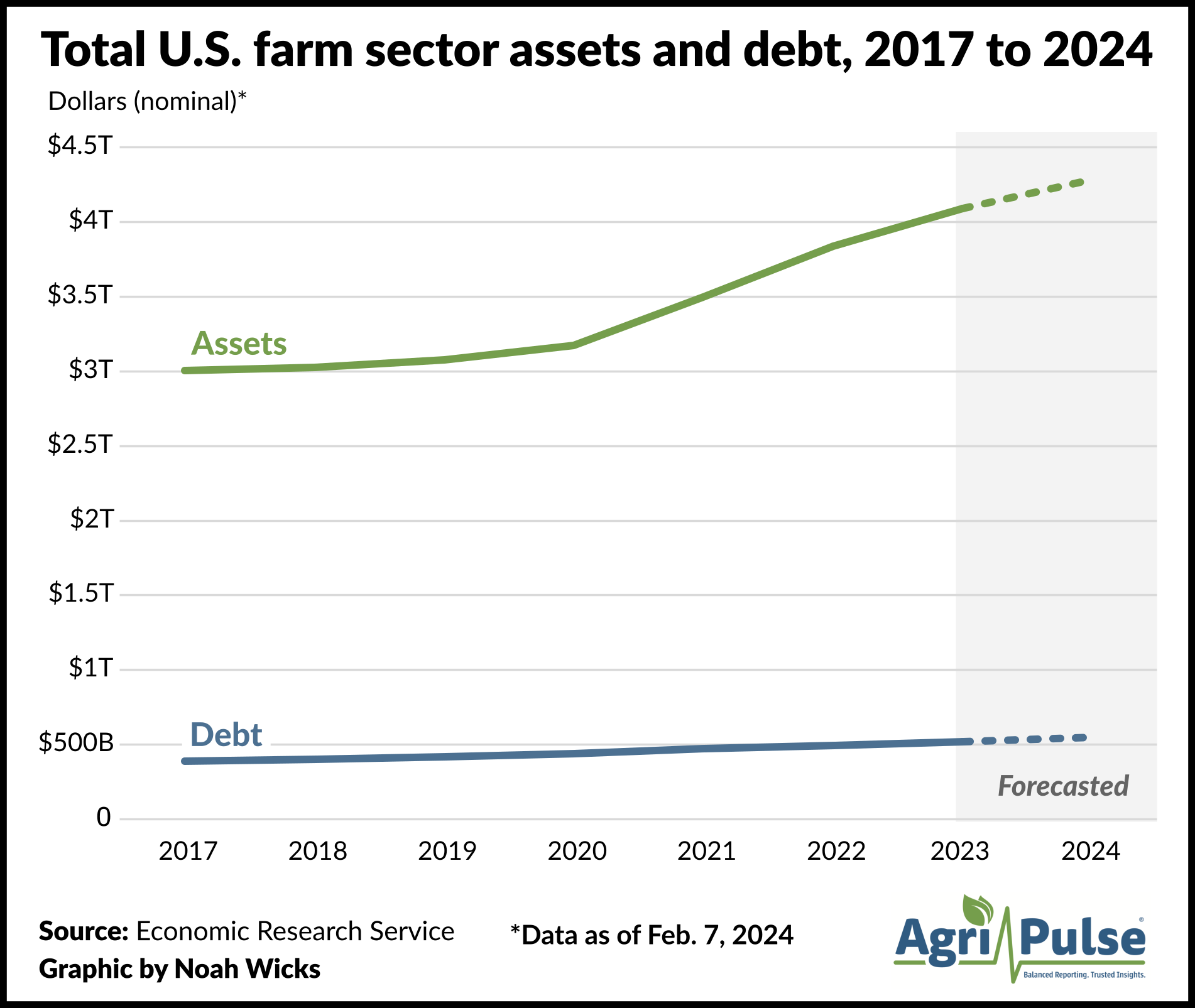

Farm sector debt is increasing, but rising asset values are helping to keep operations solvent, according to the Agriculture Department's Economic Research Service.

Total farm debt is expected to reach $547.6 billion this year, a 40% increase since 2017 and a 5.2% increase from last year. But the value of assets — real estate and machinery, for instance — is predicted to be $4.283 trillion in 2024, a 42% jump from 2017.

Rising farmland and machinery prices are one factor likely driving the growth in outstanding loans, though growing farm sizes are probably contributing, said Brad Zwilling, vice president of data analysis at Illinois Farm Business Farm Management. Low interest rates in 2020 and 2021 could have factored into farmers' decisions to take out loans in those years. The Federal Reserve began upping rates in 2022 to combat inflation.

“Debt has really been increasing,” Zwilling said of a trend he’s noticed in his home state. “The reason why debt has been increasing is because asset values have been really increasing.”

Real estate is one asset that has seen value expand the past seven years, with U.S. farmers’ land holdings going from an estimated $2.472 trillion in value in 2017 to a predicted $3.611 trillion in 2024, according to ERS data. Machinery and motor vehicle assets, meanwhile, increased from $272.3 billion in value in 2017 to a predicted $383.4 billion in 2024.

“Asset values have been relatively good, and I think you can point to farmland values on that,” said Matt Erickson, agricultural economic and policy adviser at Farm Credit Services of America. He noted that farmland prices have been holding steady amid limited supplies and interest from investors, who see land as a hedge against inflation.

Erickson added, however, that asset values can change “relatively quickly” based on a number of variables outside of a farmer's control, such as commodity prices and interest rates.

“A farmers’ balance sheet can change quickly, even if debts are unchanged,” he said.

It's easy to be "in the know" about agriculture news from coast to coast! Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news. Simply click here.

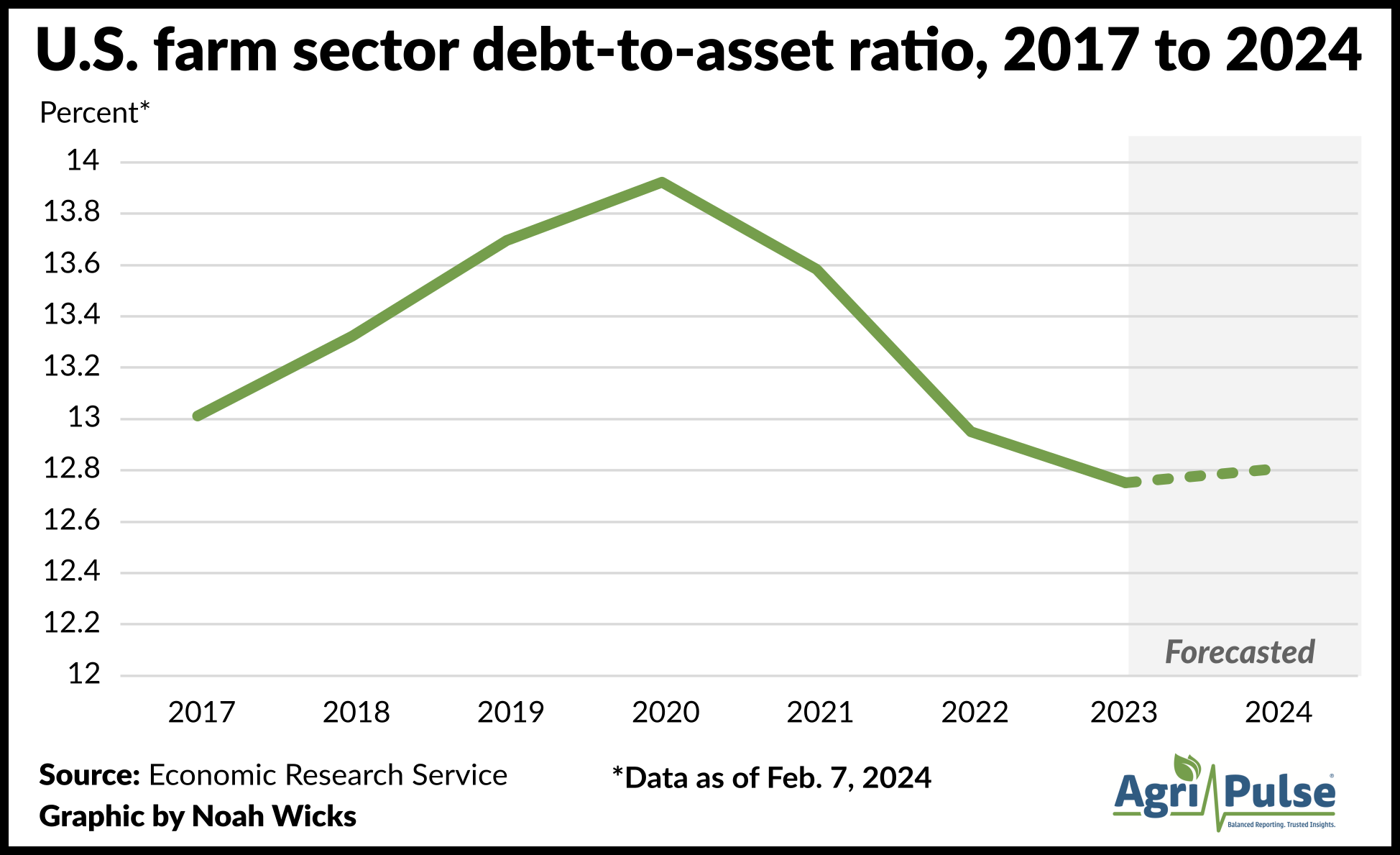

The average debt-to-asset ratio, used to gauge farm solvency, has seen an overall decline since 2017, according to ERS. It’s determined by dividing a farmer's debt for a year by the farm's assets. A lower debt-to-asset ratio is generally seen as better for farmers, as it indicates a “greater capacity to pay off debt,” according to a recent ERS report.

The average debt-to-asset ratio rose from 12.99% in 2017 to 13.96% in 2020, before settling slightly lower at 13.73% in 2023. It is expected to reach 12.78% this year.

“It’s still relatively low,” Erickson said of this year’s anticipated debt-to-asset ratio calculation.

ERS said farmers 44 years of age or younger tend to have higher debt-to-asset ratios than older producers, though debt-to-asset ratios for all age groups either fell or remained steady in 2022.

“A higher debt-to-asset ratio is OK for a young, beginning farmer, because they have a lot longer period of time to repay that debt and have a lot more earnings potential as well,” Zwilling said.

Hog, poultry and dairy operations of all sizes — small, midsize and large — had higher average debt-to-asset ratios than all farm businesses generally. Beef cattle and specialty crops were the only categories with average debt-to-asset ratios lower than the average across all sizes.

The average debt-to-asset ratios last year were 2.3% for small family farms, 5.1% for midsize units and 6.4% for large farm operations, according to ERS.

The average debt of a large family farm, classified as making $1 million or more in annual gross cash farm income, was more than $1.8 million in 2022, the report said. The average for midsized family farms between $350,000 and $999,999 in annual gross cash farm income was $783,500, while the average for small family farms earning less than $350,000 was $239,567.

Operations whose owners reported farming as their primary occupation hold 88% of the total debt in the farm sector, despite representing only 48% of all farms, ERS said. These farms, however, also hold more than 70% of U.S. farm assets.

Interest rates have also increased since the Federal Reserve increased the short-term federal funds rate between March 2022 and July 2023, which ERS says, has made farmers’ debt “more expensive.” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has said the increases were meant control inflation.

In a statement to Agri-Pulse, American Bankers Association Senior Vice President for Agricultural and Rural Banking Policy Ed Elfmann said the U.S. is seeing “a return to the cyclical ag conditions that were present before the surge of government support during the pandemic." Farmers have “worked through the liquidity they built up over the past few years” to keep up with rising input costs and are “naturally turning to credit to finance their ag operations,” he said.

“Given they were less reliant on credit the past couple years compared to normal times, it’s not surprising that we are seeing a return to historically normal debt levels,” he added.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.