It was a clear, sunny day as Nick Nemec’s New Holland tractor was chugging across his field with a planter in tow. It was the South Dakota farmer’s first real opportunity to get his corn in the ground after rain kept him out of his fields for weeks, and he was determined to make use of it.

As the auto-steer tractor guided Nemec’s brand-new corn planter through the field on Friday morning, a GPS-based guidance system kept it tethered to a straight but invisible path. But as morning drifted into afternoon, Nemec noticed his equipment began treading back into spots he had already planted or away from those he hadn’t, leaving overlaps and gaps of up to six rows.

Then, after veering far off course, the tractor made a sudden left turn and tried to loop around in a complete circle, to Nemec’s chagrin.

“At first I thought ‘something’s wrong with the system, we need to push a certain sequence of buttons on the monitor and that’ll square things up if there’s a glitch,’” the Hyde County farmer recalled.

It was only after buying a satellite positioning system upgrade from his dealer in hopes that it would resolve the navigation issue that Nemec learned the true source of the problem: a series of solar eruptions that sent plasma hurtling into earth’s magnetosphere, creating geomagnetic storms with the power to disrupt GPS and satellite systems, power grids and radio frequencies.

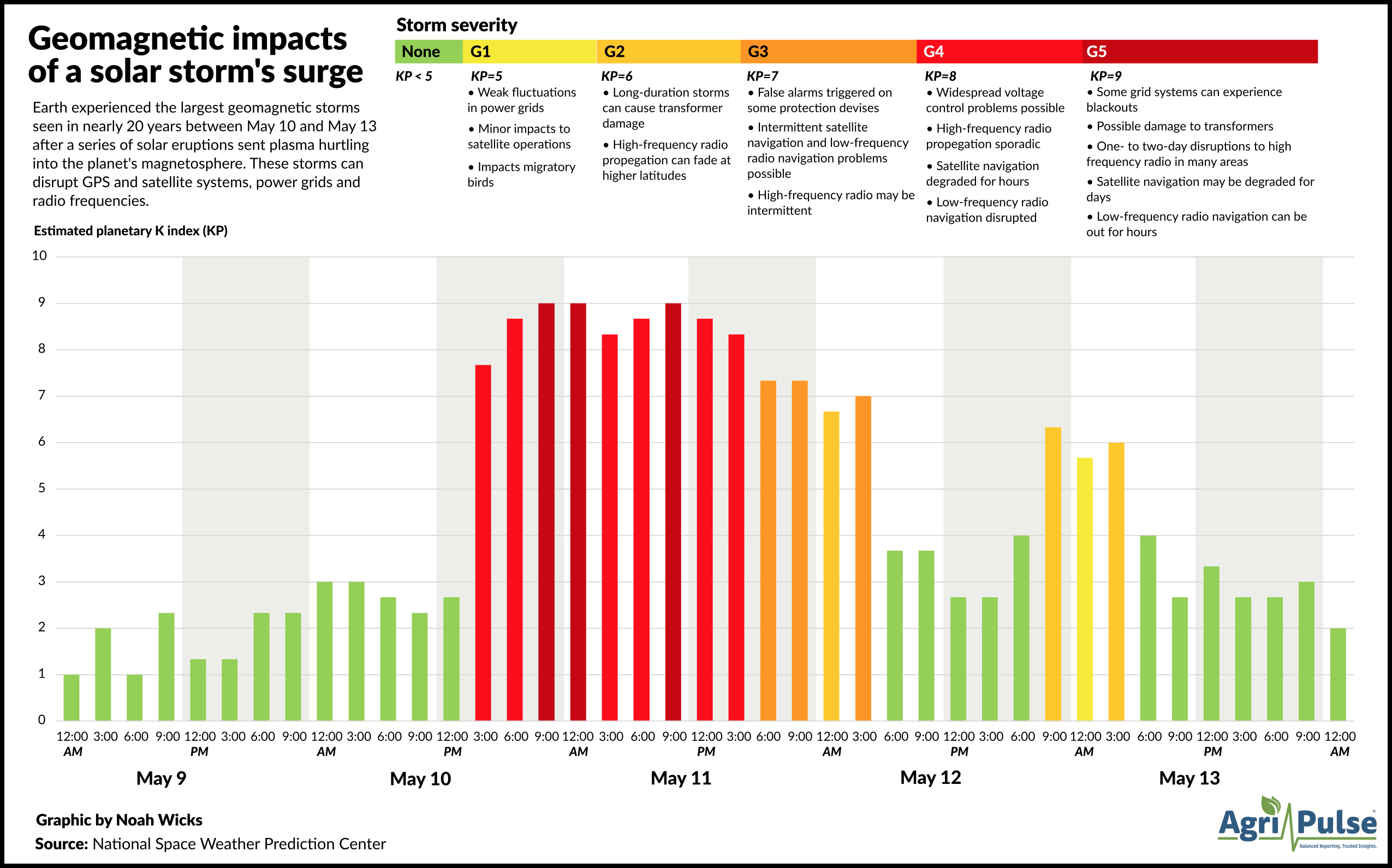

Hues of pink and green lit up night skies as far south as Arkansas this weekend as the earth experienced its largest geomagnetic storms in nearly 20 years. But farmers, who were racing to get crops seeded in decent weather with enough time to meet crop insurance deadlines, were less dazzled by the storms' other impacts as they scrambled to adjust to the messy GPS problems that hampered use of their high-tech machinery.

“You get used to certain technology, you rely on certain technology, and when it gets taken away from you, it’s hard,” Nemec said, chuckling at the bizarre nature of the situation.

When geomagnetic storms strike, they create areas within the ionosphere — a part of Earth’s upper atmosphere — that can disrupt signals between a satellite and a receiver on the ground, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration space scientist Rob Steenburgh said on a press call. He added that in severe cases, receivers can entirely lose their lock on a satellite.

The highest impact storms — ranked as G5s on the Space Weather Prediction Center’s scale — can hinder satellite navigation for days, though they only occur about four days every 11 years. Severe storms that can have hours-long impacts on satellite navigation, also known as G4s, are more frequent, happening around 60 days every 11 years.

North Dakota-based agronomist Sarah Lovas’ phone wouldn’t stop ringing after 4 p.m. on Friday afternoon, around the time the geomagnetic storms first shot up to G4 levels. Those conditions would persist through the next day, at some points even temporarily jumping to a G5 rating.

One Minnesota farmer called her because his planter wasn’t automatically adjusting the rate of seeds it was placing as it moved through various parts of the field, which the technology is supposed to do using a predetermined “prescription.” Then a North Dakota farmer dialed her up to tell her their GPS service was “terrible.”

Cut through the clutter! We deliver the news you need to stay informed about farm, food and rural issues. Sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse here.

“It is a really tough time of year for this to be going on,” said Lovas, who works for GK Technology in Halstad, Minnesota.

Farmers across the nation may have been disrupted. Roughly 12% of U.S. farms were recorded as using GPS applications in 2019, though the technology was used on roughly 40% of U.S. farm acreage, according to the USDA Economic Research Service. It has fairly wide acceptance in the Corn Belt with GPS use spanning “well over half” of the region’s agricultural acreage.

GPS technology has long been the backbone of precision agriculture, stretching back to 1993 when John Deere engineer Terry Pickett pushed the company to integrate the technology into its equipment, said former Smithsonian Institution historian Peter Liebold. It helps farmers steer equipment, avoid seeding or spraying the same spot twice, and map soils and yields.

“I would definitely say GPS is the thing that really has allowed us to do some of the stuff we do on the precision ag side,” said John Long, an Oklahoma State University associate professor of biosystems and agricultural engineering.

But farmers’ growing reliance on the technology makes them more likely to see signal disruptions when geomagnetic storms strike, though the most serious of these events are few and far between, said Kansas State University economist Terry Griffin.

“It’s not anyone’s fault,” Griffin said. “It’s just a natural thing.”

One of the largest impacts during planting season is the temporary loss of the GPS-based lines that allow farmers to plant in a precise path, setting a course within a mere inch of where they may have planted in previous years, Griffin said. Interference can not only cause crooked rows, but also limit farmers' ability to collect data that would help them to precisely spray for weeds or track yields later in the season.

Farmers can instead use planter-attached row markers to keep track of spacing, although some like Nemec removed the old-fashioned technology from their equipment after adopting the precision ag tech. Such markers can be “prohibitively expensive” for farmers with huge planters, Griffin said.

Ohio farmer Ryan Hiser pivoted to using the markers on Friday after his John Deere tractor attempted to turn in the opposite direction. South Dakota farmer Tom VanderWal also made the switch amid intermittent signal losses that sent his tractor off course, although even with the adjustment he wasn’t able to plant the variable-rate prescription he’d gotten from his agronomist.

“This is very frustrating,” VanderWal said. “We have to pay for our signal and we have to pay to have those prescriptions and it’s go time and we can’t use them because there’s a solar storm.”

When geomagnetic storms strike, North Dakota State University extension precision agriculture technology systems specialist Rob Proulx suggests farmers park their planters until the signal issues resolve. Similarly, Oklahoma State's Long said there was really not much producers can do “other than wait and see” when faced with GPS disruptions.

But time is valuable for farmers rushing to get crops in. After giving up Friday evening, Nemec reckons he lost around seven hours of planting time. North Dakota Corn Growers Association President Andrew Mauch said he knows farmers who fell back on planting by a whole day on Saturday.

Even losing half a day could mean a yield penalty if farmers are forced to make up for it late in the season, especially in northern states with shorter growing periods, Kansas State's Griffin said.

But the geomagnetic storms did afford some farmers an opportunity to see colorful auroras fill the sky when night hit. A few, like Hiser, even watched from the fields where they were working.

“It was beautiful,” Lovas, the agronomist, said of the display, though she added that she’d have preferred to see it in the winter.

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.