WASHINGTON, Aug. 2, 2016 - Democrats will be campaigning on a platform that makes the party’s most forceful case ever for taking major new steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The platform calls climate change “an urgent threat and a defining challenge of our time,” proposes to slash carbon emissions by 80 percent, and promises that doing so will create “millions of good-paying middle class jobs.”

On the convention’s final day, Gene Karpinski, president of the League of Conservation Voters, said his group’s “very top priority” is elected Clinton so she can address climate issues. “Hillary is a proven leader with a vision and plan to combat climate change and to make America the clean energy superpower of the 21st century.

But getting any major action on the

issue through Congress in the foreseeable future is likely to be impossible,

and not just because Republicans are likely to retain control of the House and

have, at the worst, a strong minority in the Senate. There are also some doubts in the Democratic base about the idea that

climate legislation will produce that many middle class jobs.

But getting any major action on the

issue through Congress in the foreseeable future is likely to be impossible,

and not just because Republicans are likely to retain control of the House and

have, at the worst, a strong minority in the Senate. There are also some doubts in the Democratic base about the idea that

climate legislation will produce that many middle class jobs.

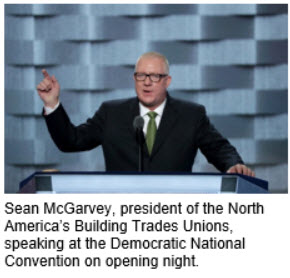

Sean McGarvey, president of the North America’s Building Trades Unions, an umbrella organization for construction unions, says that renewable energy projects often pay a fraction of what construction workers can earn in fossil fuel industries or on nuclear projects, such as the one Southern Co. is now building in Georgia.

McGarvey is no Republican. He gave a speech in support of Hillary Clinton during the convention’s opening night. He said she “has the boldest infrastructure plan we’ve seen in generations. She will help us repair roads and bridges, make broadband universal, build new airports, and modernize our energy grid.”

But McGarvey’s organization supported construction of the Keystone XL pipeline and lashed out at environmental groups for successfully lobbying the Obama administration to kill the project. During an energy policy forum on the sidelines of the Democratic National Convention last week, McGarvey cited an Energy Department estimate that solar panel installers are paid only about $16 an hour.

The message that McGarvey’s union members are getting is this, he said: “We’re going to transition you not out of fossil fuel jobs that have kept you securely in the middle class for generations into the renewable future and by the way we’re going to cut your wages by three quarters.”

McGarvey also delivered a thinly veiled warning that Democrats would continue to struggle to reach economic struggling workers if the party continued to give in to pressure from what he called the “radical environmental community.”

“A lot of the consternation in the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign right now is how do we reach these disaffected workers in the country,” McGarvey said, referring to the campaign’s struggle to appeal to workers in states such as Pennsylvania, where Democrats are widely accused of killing the coal industry

There are clearly differences in pay scales between energy sectors: According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average hourly wage for solar installers is $19.26, and the annual salary was $40,070. By comparison, workers who operate or maintain machinery in power plants earned on average $34.17 an hour, or $71,070 a year. Wind turbine service technicians earned $25.50 per hour or $53,030 a year. Workers who operate petroleum refining equipment earn $31.74 an hour, or $66,020.

Labor analysts at the University of California, Berkeley, say that workers on utility-scale solar projects where jobs are often unionized earn far more than roof-top installers, whose wages are tied to residential construction pay scales. Hourly wages for installers in California range from $11.50 to $21 an hour, while utility-scale construction jobs in the state pay $39 per hour on average, or $78,000 per year.

Rooftop solar companies” essentially compete in the residential construction market where barriers to entry are low, unionized contractors are absent, and contractors who comply with employment laws and building codes must compete with many who skirt these regulations,” the analysts wrote. “All of this puts downward pressure on wages.”

Wages in the solar industry would improve if there were union representation, better enforcement of labor laws, skill certification requirements, the analysts said. “While climate policy is not a jobs program, the particular mix of strategies and public investments that we choose to meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals do have an influence over the types of jobs that are created.”

What the analysts didn’t say is that raising wages would also increase the costs of solar and other renewable energy projects, something investors in renewable energy projects resist, according to McGarvey.

The potential political problem for Clinton and congressional Democrats is how to manage the pushback from labor. (Democratic divisions aren’t new when it comes to energy policy; they doomed President Obama’s cap-and-trade plan in the Senate in 2009-10, a period when Democrats controlled both chambers.)

The striking thing about McGarvey’s comments at last week’s Bipartisan Policy Center event was not just his point about disparities in pay scales, but the fact that his comments came in a sharp exchange with one of the Senate’s most outspoken proponents of climate action, Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., in front of a panel that included Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz and former Sen. Tom Dachle, D-S.D.

During the forum’s Q&A session, Whitehouse, who was in the audience near McGarvey, stood to deliver an attack on the fossil fuel industry and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which the senator said had managed to silence Republicans and make climate policy a partisan issue.

“This is old school, special interest special pleading. They’ve made it work by masking it in the partisan fight,” Whitehouse said.

Daschle acknowledged Whitehouse’s concern about the impact of industry spending. “We all have to understand how critical it is that we deal with the money in politics and governance today,” Daschle said.

But a few minutes later, McGarvey rose to challenge Whitehouse directly. “It takes two to tango. … The radical environmentalist community and their funders in this county have put Democrats on the defensive” the same way the fossil fuel industry has influenced Republicans he said.

Whitehouse tried to interrupt to say that there was no comparison between the influence of environmentalists and the fossil fuel industry, but McGarvey brusquely cut the senator off in a way that only a union leader could probably get away with. “I’m speaking now. I have the floor,” McGarvey said. Whitehouse said nothing more.

“There’s got to be some way for this transition to happen, whether it’s 20 years or 30 years, where we not only raise the wages in the renewable industry but we lessen the blow as people come out of the fossil fuel industry,” McGarvey said.

He went on, “We want to be engaged and part of the solution, not part of the problem. But somebody has to figure that out.”