WASHINGTON, March 30, 2016 - (Editor’s Note: I was invited to share some of the national and international trends that can impact agriculture as a kickoff to this meeting, “Shaping Our Own Destiny, The Future of Agriculture in Pickaway County,” on March 17. As someone who has watched urban sprawl take over hundreds of thousands of acres of prime farmland in many parts of the country, this was a chance to see how local leaders could protect agriculture but still embrace economic development. My report follows.)

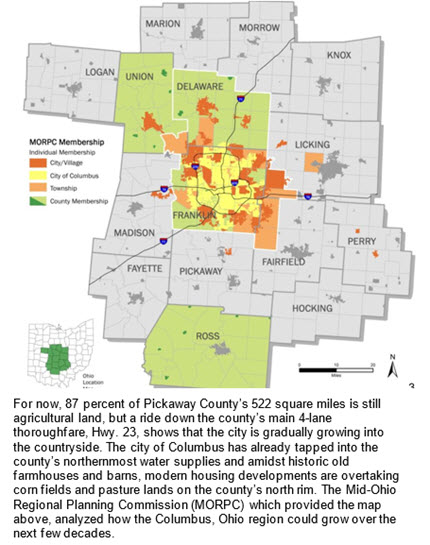

Columbus, Ohio, is a city on the move – adding jobs, shopping areas and expanding its Franklin County footprint to surrounding areas. Recent projections indicate that 500,000 more people will live in the 11-county region anchored by Columbus by 2050, a growth rate of 25 percent or more. And demographics are changing, too, with the projected increase coming primarily from the “older baby boomer” generation – those 65 years or older who are looking to retire -- as well as 16-34 year olds who want education and economic opportunities.

That growth curve could bring both good and bad news for neighboring counties like Pickaway - located about 15 miles to the south of that expanding urban area where the footprint is overwhelmingly (87 percent) still in agriculture. That’s why a group of farm, city and county leaders – organized by Ohio State Extension Educator and County Director Mike Estadt and others -- recently joined forces in their county seat, Circleville, to map out their future.

The group of about 60 local residents included farmers, economists, county commissioners, business development specialists and civic leaders. Their ages ran from 17 to over 80, providing for an interesting and often refreshing breadth of perspectives.

“We’re at a place in time to do some really great things or really screw things up,” noted one of the participants. “But I don’t want to look back 20-25 years from now and regret that we didn’t try.”

A core group of leaders had already done their homework – participating in a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis, surveying the group about how they view their future and, in this session – breaking into small groups in an attempt to share ideas and prioritize.

Throughout the discussions, the need for comprehensive county planning, education and creative thinking came through loud and clear. There was talk of breaking down barriers and sharing more resources. For example, some expressed the need to have area-wide funding for emergency responders instead of those hosted by every township.

“We can’t afford to have everything structured the same way that we’ve had it in the past,” said Shirley Bowser, a local farmland owner and philanthropist.

But then more difficult questions emerged. Which local

townships or local school districts would be willing to give up control? Which

county leaders will step up and make the tough choices needed to advance some

of the interests expressed? If more education about the benefits of keeping

agriculture in the county is needed, who is going to pay for the effort and who

is going to do the work?

to advance some

of the interests expressed? If more education about the benefits of keeping

agriculture in the county is needed, who is going to pay for the effort and who

is going to do the work?

It’s not an easy process to bring people with distinctly different viewpoints together. But it’s a much needed effort that every county in the country probably ought to undertake – whether they are dealing with too much growth or too little, noted Bobby Moser, a former dean of agriculture at Ohio State who participated in the discussion.

Indeed, the majority of rural counties – the 1,300 that witnessed population declines from 2010-2014 – are struggling with an opposite problem: how to create jobs and bring people back into their regions. Yet, nearly 700 rural counties - primarily those in scenic or booming areas like central Ohio– added over 400,000 people during that same time period. They face some of the same challenges as Pickaway County.

Managing growth within a county can be a balancing act, noted Bill Richards, whose picturesque farm is located outside of Circleville. The no-till pioneer loathes the idea of paving the prime farmland spread throughout Pickaway County, but he also understands that manufacturing and service jobs are good for the county’s tax base. Plus, new jobs benefit city folks as well as farm families who need to earn off-farm income to start their own businesses and support their families.

Richards applauded the county’s recent economic development efforts to recruit a new Italian paper processing firm, Sofidel, and a local Christian college that plans to create a business incubator program.

“I’ve driven through county seats all across the country and you can pretty much tell what kind of political management they have by looking at their downtowns,” he adds.

But more employment could bring in people who don’t understand agriculture. These newer rural residents may not want a dairy or hog operation next door -- and that could also threaten the goal of preserving agriculture in the county. Population growth also requires more roads and bridges, emergency services and schools – all of which requires a broader tax base and other new revenue sources.

“Economic development and agriculture don’t have to be at odds,” said Ryan Scribner, economic development director of the Pickaway Progress Partnership, who’s charged with recruiting new businesses to the area. He sees the challenge ahead as a “big, blank palette. We just have to decide what colors we are going to use.”

At the end of the day, Estadt said there was consensus from the group about the need to do more education and networking. The younger members would like to put together a presentation on what they learned and share their thoughts with other governmental entities. As one participant noted, “If agriculture is not at the table, it could be on the table.”

#30

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com