WASHINGTON, Sept. 2, 2015 - Not unlike the long-term laboratory and field successes in improving corn and soybeans, American scientists, sugar cooperatives, seed companies, farmers and others have been steadily adding magic for a half century to sugar beets and the techniques in growing them.

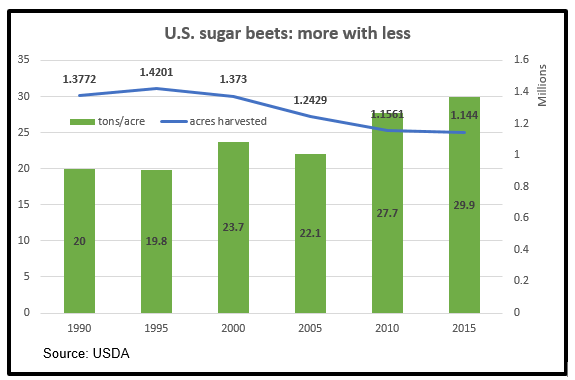

Crop yield is one good measure of how well they’re doing. So let’s go to the numbers. The 2015 U.S. average corn yield is projected at a near-record 169 bushels per acre, up 42 percent since 1990, while the soybean yield is seen at 47 bushels, up 38 percent since then. This fall’s sugar beets, meanwhile, are pegged by USDA at 30 tons per acre. That’s up 50 percent since 1990, yet more in terms of sugar per acre. That’s because the beets’ sugar content, in annual statewide averages, has edged up to 17-19 percent from 16-17 percent in the early 1990s. So, tally sugar beets for about a 55 percent rise in output of refined sugar per acre.

The mounting yields have let U.S. farmers keep upping their output even though harvesting fewer and fewer acres: about 1.1 million acres this fall, down from 1.4 million in 2000. This is largely because U.S. sugar beet and cane growers face mounting market pressure from sugar imports and must limit their output to national marketing quotas. The beet growers contract their crops to processing cooperatives and target their production to the processing plants’ capacity. Cane growers, who are projected to account for 43 percent of U.S. production in the year ahead, also limit their output.

down from 1.4 million in 2000. This is largely because U.S. sugar beet and cane growers face mounting market pressure from sugar imports and must limit their output to national marketing quotas. The beet growers contract their crops to processing cooperatives and target their production to the processing plants’ capacity. Cane growers, who are projected to account for 43 percent of U.S. production in the year ahead, also limit their output.

In eastern Michigan, Paul Pfenninger, agriculture vice president for Michigan Sugar Company, projects the harvest now under way will average a record 31.15 tons an acre, and he expects the sugar content will hit “19 percent, or over 19 percent . . . for the majority of our crop,” which is harvested in October and early November.

Pfenninger details a fistful of reasons that beet yields keep climbing. Since the 1960s, USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) personnel have been working with beet germplasm and the pathogens that attack beets, sending new strains and findings on improved growth and disease resistance to seed companies, state university researchers and others to improve beet seeds.

Kimberly Webb, a plant pathologist at the ARS station in Fort Collins, Colorado, summarizes her research as working “to better understand how plant diseases occur in the field and how they interact with sugar beets.” She is focusing on fusarium yellow, which thrives in beet roots and clogs the plants’ vessels.

Meanwhile, a plant breeder at the Fort Collins site is improving beet germplasm to resist the virulent cercospora leaf spot fungus, and scientists in ARS stations in Kimberly, Idaho; Fargo, North Dakota, and elsewhere are working with beet germplasm to improve other traits.

In Michigan, Pfenninger says plant experts in his co-op’s own nurseries, too, work to strengthen resistance to diseases. He says that the beet growers’ buyout of two sugar companies about a dozen years ago to form MSC, a consolidated cooperative that processes a billion pounds of sugar annually, “opened doors and avenues for us” to improve breeding, planting and raising the crop, transporting and storing it, processing it and more.

Production gains for MSC members include countless advancements in field equipment and farming practices, he says. Simply narrowing the space between rows from 30 inches to 20-22 inches boosts a field’s beet population per acre substantially, for example. And the arrival of glyphosate-tolerant varieties about eight years ago means what had been the typical eight to 10 passages of cultivating and spraying equipment over the field each year is now often just two passes to spray the broad-spectrum weed killer, reducing operating costs and damage to beets.

But Pfenninger and Brian Ingulsrud, the agricultural vice president for American Crystal Sugar Co. in Minnesota and North Dakota, say the foremost enhancements for sugar beets have been with seeds – including the genetics, seed treatments and how they are put into the soil. For decades, perhaps the biggest challenge in growing beets was in the emergence stage: in germination and the start of vigorous seedlings. “The seed companies have done a terrific job in seed treatments” that enhance germination, protect seeds from soil-borne diseases and insects, and speed early growth, Ingulsrud says.

And on the farm, “We have to credit the growers and their preparation of the seed bed,” Ingulsrud says, because soil conditions are so important to a beet’s strong start. Just as critical, he says, are the many improvements in planters, allowing seeds to be placed uniformly, at the proper depths and with the proper covering. Several such planter design improvements have made a difference, he believes.

#30

For more news go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com