WASHINGTON, May 6, 2015 – While the historic bird flu outbreak now afflicting the nation’s poultry producers may abate with advent of summer and warmer temperatures, the effects of the highly pathogenic H5N2 strain of the virus may be felt in production and markets through Thanksgiving and into next year.

As of May 4, USDA said that it had confirmed more than 120 detections since early January affecting almost 24 million birds, all of which have died or are being euthanized to arrest the spread of the disease. That is about 7 million more than in the last major outbreak of the highly pathogenic H5N2 outbreak in 1983-84.

Although the virus has been found in more than a dozen states, it has focused its fury on turkey and laying-hen flocks in Minnesota and Iowa. Animal health experts note that the virus is now present across the middle of the Mississippi River migratory flyway, so it could easily be carried across a huge swath of the continent next fall and winter by wild birds returning south, and among poultry farms by other means, including on trucks and farm equipment.

The turkey sector is the hardest hit in terms of the share of total flock: About 5 million turkeys on infected farms, or 5 percent of the U.S. inventory, have been “depopulated” and lab confirmations are being reported almost daily. In Minnesota, the nation’s biggest turkey-producing state, the toll is already close to 4 million – or nearly 20 percent of its flock.

Tom Elam, an analyst with the National Turkey Federation, said that ducks, geese and other wild birds transmit the virus but are less affected and “carry the flu viruses with much better resistance that our kept birds do.” He points out that the virus “has just happened to hit in an area that is very concentrated in turkeys,” and the cold weather seems to have accelerated its spread.

Beyond the sizable share of the turkey flock hit by the virus, recovering full production will likely take a half year or more, Elam said. First, that's because the U.S. turkey inventory had fallen to a low ebb by late last year. Since then, producers, enticed by the tight market and record prices, had ramped up hatchings and chick placements by 5-8 percent through March.

Beyond the sizable share of the turkey flock hit by the virus, recovering full production will likely take a half year or more, Elam said. First, that's because the U.S. turkey inventory had fallen to a low ebb by late last year. Since then, producers, enticed by the tight market and record prices, had ramped up hatchings and chick placements by 5-8 percent through March.

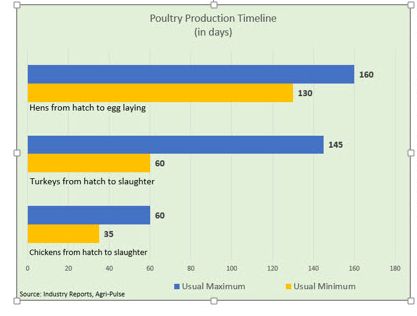

“But all those extra poults were already going to be needed,” he says, just to produce last year's level of output, about 237 million birds. What's more, feeding turkeys to slaughter size takes much longer than for chickens (see graph on left).

Look for wholesale turkeys to continue at or above their unparalleled prices – frozen hens about $1.05 a pound; fresh, about $1.17, which is around a dime more than the record prices of a year earlier.

H5N2's impact on the egg industry is hefty, too. Production in California, the top egg-consuming state, had already dropped this year as new regulations on housing hens were implemented and some farms shut down. Now, the virus has generated a poultry disaster in Iowa, wiping out more than 16 million laying hens, which is more than a fourth of the top egg-producing state's flock. It is also over 5 percent of the U.S. inventory.

USDA economist Alex Melton says the industry is likely to adjust within months if the outbreak abates quickly. He notes that egg farmers had already ramped up hatchings of laying hens – by 14 percent in March, the latest count, versus a year earlier. So egg production was on track for expansion and egg prices remain strong: The U.S. wholesale average for extra-large eggs is normal for the post-Easter market; in California, still more than $1.50, up 30-40 cents from a year ago.

Nonetheless, constraints on exports are affecting prices for dark chicken and turkey meat, the cuts that dominate U.S. exports. USDA's Melton notes that while whole-bird and breast meat prices remain strong (breasts now $1.50 to $170 a pound) leg quarters have plunged to as little as 27 cents a pound in the wholesale market, the lowest in five years. Turkey drumsticks, meanwhile, are only about 62 cents a pound, down from 95 cents a year ago.

Here’s why. All poultry export markets are under varied amounts of duress from importing countries, including from some large buyers such as China and South Korea that started announcing bans early this year when H5N2 first appeared in the U.S. The chicken meat sector is thus taking a hit even though it's been spared H5N2 so far because most of the nation's broiler chicken farms are in the southern and East Coast states, which the outbreak has spared.

Poultry meat exports were down 11 percent in the first two months of 2015 (April trade data won't be out till summer). Toby Moore, spokesman for the USA Poultry and Egg Export Council, says the foreign bans will likely continue through this year. On the other hand, Mexico, the largest U.S. poultry export market, continues to import all chicken and turkey meat that goes directly to Mexican processors, which includes most of usual shipments there. “Mexico has been sort of our saving grace. We've retained out biggest market,” Moore says.

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.