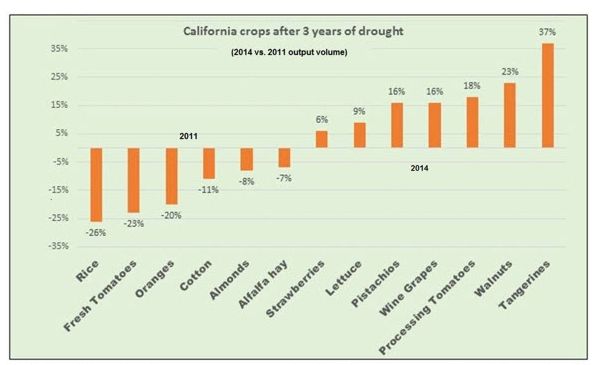

WASHINGTON, April 15, 2015 – Is California's severe drought a total disaster for its farm sector? Not generally. In fact, the output of several major crops in the Golden State is climbing while others have fallen (see chart below) as the drought, which began moderately one in 2012, continues to tighten its grip. What's more, even with the latest dire projections for another very dry year there, output will likely continue at a fairly steady pace. And what's usual for California, the nation’s leading agricultural state, is nearly an eighth of U.S. farm production by value.

The worst of California's drought is in the San Joaquin Valley, the southern portion of the state's huge, largely agricultural, Central Valley. For its water, it is highly dependent on the Sierra Nevada snow melt, which will be but a trickle this year.

Little wonder then that House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, who hails from the Central Valley, is working on a federal drought relief package. Last week he said that House Republicans are developing a new legislative proposal to help put California water policy “back on the path to common sense.”

Dave Kranz, communications director for the California Farm Bureau Federation, says most of that area's farmers are diversified, and they've been making difficult, costly adjustments since the drought took hold. They're leaving fallow a lot of land that lacks a source of water and, instead, consolidating operations and switching to new tracts, “focusing on keeping their trees and vines, at minimum, alive, and at maximum, producing full harvests.”

Illustrating his point, Kranz says, are processing tomatoes – grown across a big swath of the Central Valley and used for juice, sauces and paste. Many farmers switched cropping to more water-secure land last year and were able to boost their deliveries by 2.1 million tons, despite the drought. Now, processors report they've contracted for 15 million tons this year – up by a million from 2014.

Such switching of commodities is widespread. Since the drought has set in, Kranz says, up and down the San Joaquin Valley farmers have been bulldozing orchards of old, declining almond, walnut and orange trees and planting new tracts of the same or other crops. “You're going to see more of that this year and in the future,” if drought continues, he says.

The replacement of almond trees is, in fact, causing total annual volume of the state’s most valuable crop to decline, mostly because small young trees produce far less than old established ones. So while growers have expanded overall bearing acreage by at least 8 percent since 2011, the 2014 harvest was about 8 percent less than in 2011. But since California raises most of the world's almonds, 2014's smaller harvest has sparked record almond prices of over $3.50 a pound on export shipments, more than twice pre-drought prices.

The state's shifts in crop acreage are also geographical: Both almond and grape operations are shifting north and west, where rainfall is more ample and groundwater more accessible. As with almond trees, huge tracts of grape vines are being cleared in the San Joaquin Valley, where most grapes are grist for cheap wines, raisins and table grapes. New tracts of vines for making high-value wines, on the other hand, are being planted in the northern Central Valley and central coastal region.

California's commercial grape production (all types of grapes) spiked to 4.7 billion tons in 2013, then fell to 4.1 billion last year. But Jeff Bitter, vice president of Allied Grape Growers, says growers cut back because there were too many low-value grapes – not because of the drought. Total bearing acreage for wine varieties, the dominant type of California grapes, will be back up a little this year, thanks to surging consumer demand for high-value wines, prompting expanded acreage in the central coast and northern Central Valley regions that grow those varieties. And as with almonds, the constrained acreage is paying off in the market: Growers saw record prices, averaging about $750-$950 a ton, for their 2014 wine grapes.

It turns out that production of most fresh fruit and vegetables in California is either steady or rising to meet demand. That's true for strawberries, for example, grown in coastal farming areas and producing over $2 billion in annual sales for growers. Caroline O'Donnell, speaking for the California Strawberry Commission, says growers exclusively drip irrigate and mostly from wells. They've trimmed plantings from a peak of 40,800 acres in 2013, owing mainly to scarcity of farmworkers and stringent environmental and food safety regulation, not to water shortages. She says growers “are certainly anxious for rain to replenish the groundwater.” But, thanks largely to adoption of new higher-yielding varieties in the past few years, annual harvests have continued at around 27.6 million hundredweight the past three years.

Nonetheless, the drought is squeezing the acreage of a few bulky field crops that deliver only modest profits per acre but suck up a lot of water. California's cotton harvest plunged from 454,000 acres in 2011 to just 210,000 last fall, and farmers told USDA they'll seed 27 percent fewer acres this year. Rice acreage has fallen by 150,000 since 2011, and alfalfa has dropped by 400,000, and will slip more this year.

The state's cattle inventory, meanwhile, has not receded overall since 2011, despite the triple whammy linked to the drought: parched pastures, high feed and forage prices plus expenses for new and deeper wells to sustain herds and flocks. Rather, the state's cattle inventory, 5.25 million, is the same as in 2011, even while the national herd has shrunk.

But the long and steady expansion of California's dairy industry, for decades the nation's biggest by far, has stalled out. Farmers are still milking nearly 1.8 million cows, same as a year ago, but milk per cow and total production are both down 3 percent to 4 percent so far this year versus a year earlier.

“There are a lot of reasons going into the cutback on dairy farms,” says Rob Vandenheuvel, general manager of the California-based Milk Producers Council. Overall, he says, “the farmers' costs are so significantly higher than the prices they're getting for milk.” While costs have jumped, the milk market in California is significantly stingier to farmers than elsewhere in the country. He points out that the “all-milk” price to farmers is running about $13 a hundredweight in California, which is about 20 percent less than the U.S. average. “Our industry is in much tougher position than a year ago when milk prices were higher,” he says.

#30

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.