The Supreme Court’s Clean Water Act decision restricting the federal government’s jurisdiction over “adjacent” wetlands prompted warnings that millions of acres of wetlands could be at risk, but the ruling generated cheers from farm groups that have fought for decades to limit the interpretation of the 50-year-old law.

It also may be the death knell for what remained of Chevron deference, even before the court takes up that specific issue in a later case. The Chevron doctrine says when a law is ambiguous, courts should defer to federal agencies’ interpretation.

Travis Cushman, deputy general counsel at the American Farm Bureau Federation, said the decision in Sackett v. EPA was "the exact result we were looking for."

“It makes it much easier for farmers and folks in the field to walk out and know, just by looking at the property, whether or not something should be regulated as a water,” he said in an interview with Agri-Pulse.

Cushman said the way the opinion’s result has been reported – as a 5-4 decision – is misleading because all nine members of the court rejected the federal government’s “significant nexus” test, which was crafted by former Justice Anthony Kennedy in the 2006 Rapanos decision.

That test said wetlands could be regulated if they “either alone or in combination with similarly situated lands in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity” of navigable waters.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan did not say how the agency would respond to the decision. EPA is facing court challenges that have already resulted in its latest rule, which relies on the significant nexus test, being temporarily blocked in 27 states.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan“We’re still combing through the implications,” Regan said. “There’s no doubt that we are very disappointed, but we’re going to take a closer look at what the ruling actually means. We’re going to continue to work as hard as we can to follow the law but also to protect all communities and provide safe, affordable drinking water for every community in this country. That is our goal."

EPA Administrator Michael Regan“We’re still combing through the implications,” Regan said. “There’s no doubt that we are very disappointed, but we’re going to take a closer look at what the ruling actually means. We’re going to continue to work as hard as we can to follow the law but also to protect all communities and provide safe, affordable drinking water for every community in this country. That is our goal."

One option would be for EPA to simply withdraw the rule and ask the courts now handling the litigation to allow EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers to come up with a new rule.

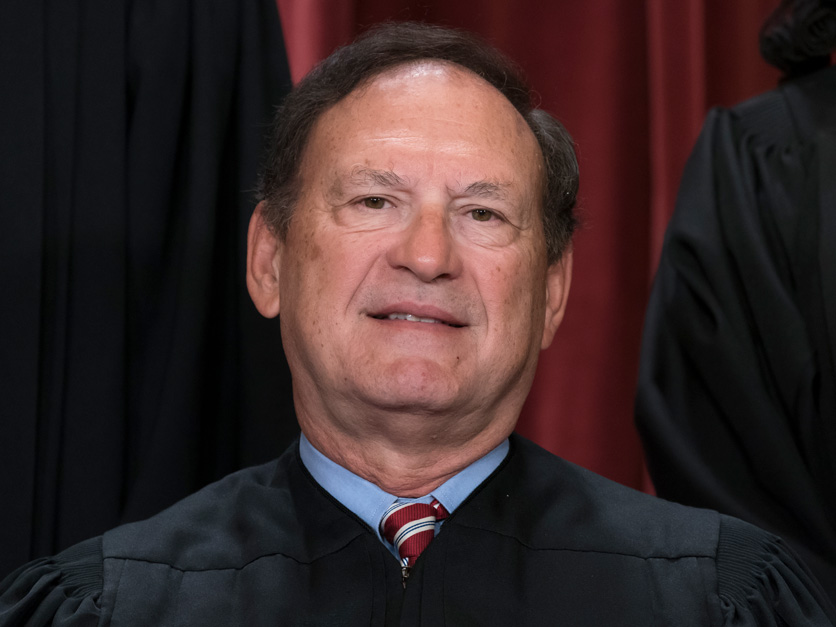

There were no dissents to the majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito and joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Amy Coney Barrett, and Chief Justice John Roberts.

Instead, the other four justices concurred in the judgment – that the wetlands on the Idaho land of Michael and Chantell Sackett are not jurisdictional – but said the majority’s interpretation went too far.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in a concurring opinion joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, said the majority engaged in a “rewriting” of the law by interpreting “adjacent wetlands” to mean “adjoining.”

Alito's majority opinion said adjacent wetlands have to be close enough to other waters covered by the CWA as to be “indistinguishable.” It also said the significant nexus test results in an “unchecked definition of ‘the waters of the United States’ [which] means that a staggering array of landowners are at risk of criminal prosecution or onerous civil penalties.”

Kavanaugh, however, noted that in 1977, Congress added “adjacent” wetlands to the definition of “waters of the U.S.” in the law.

Since then, “the Army Corps has adopted a variety of interpretations of its authority over those wetlands – some more expansive and others less expansive,” Kavanaugh wrote. “But throughout those 45 years and across all eight Presidential administrations, the Army Corps has always included in the definition of ‘adjacent wetlands’ not only wetlands adjoining covered waters but also those wetlands that are separated from covered waters by a manmade dike or barrier, natural river berm, beach dune, or the like.”

“I would stick to the text,” Kavanaugh said. “There can be no debate, in my respectful view, that the key statutory term is ‘adjacent’ and that adjacent wetlands is a broader category than adjoining wetlands.”

The decision also is another sign that the court is close to formally reversing the Chevron doctrine.

The court has already signaled its lack of respect for agency interpretations of existing law, ruling in a case last year that EPA exceeded its authority in regulations designed to curb greenhouse gas emissions from power plants.

In the Sackett decision, the court specifically said it would not defer to EPA’s rationale that wetlands can possess a “significant nexus” to “navigable waters” even if they are separated from jurisdictional waters by a berm or a dike.

The decision “is a clear indication, once again, that the court is not going to rely on deference doctrines as it has done in the past,” said Matthew Leopold, a lawyer at Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP and a former EPA general counsel who helped write the Trump administration’s Navigable Waters Protection Rule. That regulation was struck down by the courts in 2021, setting the stage for the Biden administration rule.

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)Leopold noted that the court will hear a case involving Chevron in the fall. Chevron is “not dead at this point, (but) is mortally wounded," he said.

“The Supreme Court is not going to allow vague statutory language to be the basis for broad and impactful, far-reaching programs,” Leopold said.

The result of the Clean Water Act ruling is that “we're going to see, undoubtedly, millions of acres of wetlands and ephemeral and, potentially, intermittent streams that are impacted negatively,” said Marla Stelk, executive director of the National Association of Wetland Managers.

Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law firm, estimated that more than half the approximately 118 million acres of U.S. wetlands are now at risk.

Don’t miss a beat! It’s easy to sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! For the latest on what’s happening in Washington, D.C. and around the country in agriculture, just click here.

“We’re going to see a lot more water quality issues, we're going to see a lot more fragmentation of habitat,” Stelk said.

“Essentially, what Alito has said in his opinion is that science doesn't matter,” Stelk added. “We're kidding ourselves to think that we can create effective policy and legislation that deals directly with a science-based system without taking the most up-to-date, peer-reviewed, universally acknowledged science that's out there on those systems. We might as well just throw ourselves back into the Dark Ages.”

Kavanaugh said the court’s new “continuous surface connection” test “not only will create real-world consequences for the waters of the United States, but also is sufficiently novel and vague (at least as a single stand-alone test) that it may create regulatory uncertainty for the federal government, the states, and regulated parties.”

The court also affirmed that states have the “primary” responsibility to prevent water pollution, citing a brief filed by state Farm Bureaus that had argued the same.

“States can and will continue to exercise their primary authority to combat water pollution by regulating land and water use,” the majority said.

Proponents of limiting EPA’s authority have argued that states are fully capable of protecting their own resources – not a notion that environmental groups or Stelk agree with.

Under the CWA, states can get EPA authorization to take over wetlands permitting. which is generally handled by the Corps of Engineers. Three states currently have such authority – New Jersey, Michigan and Florida.

"We're looking at this as an opportunity to get more incentives to states and tribes to help them identify waters of the state or waters of the tribe, or however they want to do that, and apply for state assumption in the 404 program," she said, referring to CWA Section 404, which covers wetlands permitting.

The one “silver lining” in the decision is “this gives us a good argument for advocating for wetland program implementation funding” at the state level," Stelk said.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.

This article has been corrected with the correct name of Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP.

![Steve headshot 250x200[1]](http://www.agri-pulse.com/ext/resources/Headshots/Staff-Photos/thumb/Steve_Headshot_250x200[1].JPG?1738947158)