The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee has been charged with examining diet and nutrition through a “health equity lens,” which is encouraging news for anti-hunger advocates. But the dairy industry is trying to head off the possibility that recommendations could be modified due to concerns about lactose intolerance in minority populations.

Anti-hunger advocates, who have long pointed out the role of income and race in determining both availability and variety of food choices, have welcomed the announcement of the DGAC's membership.

The 20 DGAC members include at least three with specific expertise in the area of health equity, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and numerous public health groups as ”the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health.”

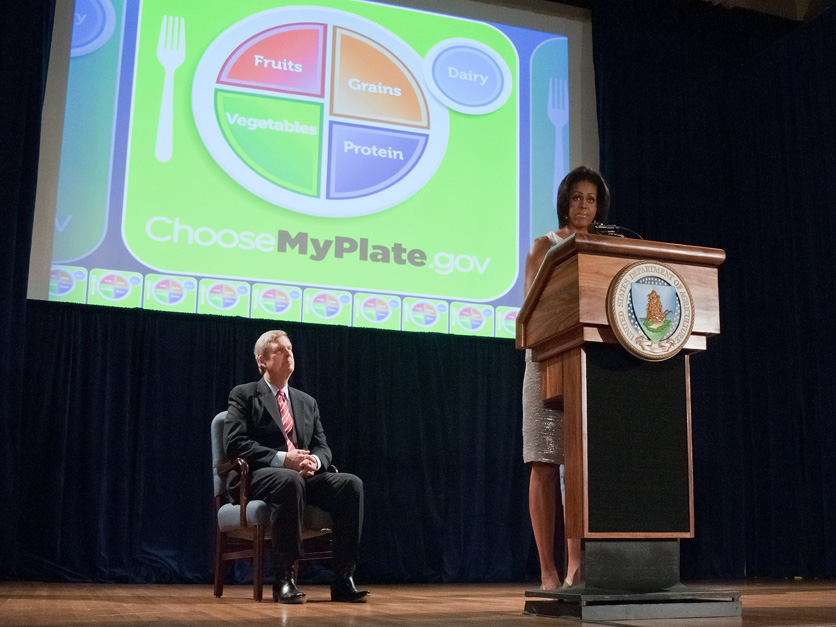

The guidelines shape the school meals program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Spending data supplied by the Food Research & Action Center, based on information from the Food and Nutrition Service, show that in fiscal 2021, USDA nutrition programs including school meals, after-school, child and adult care, SNAP, Pandemic-EBT, and WIC distributed $182.5 billion in food benefits, food, and food service funding, or 9% of the total food spending by consumers, business and government.

What the equity focus will mean for the advisory committee as it begins its work next week has not been completely fleshed out. The DGAC is currently looking at scientific questions proposed by the Department of Health and Human Services and USDA and “updates to the scientific questions will be discussed during committee meetings,” HHS spokesman Daniel Hirsch said.

But the agencies have provided some details in questions and answers posted on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans website. A critical first step, they said, is a DGAC “that has a diverse membership with respect to points of view, expertise, experience, education, and institutional affiliation to reflect the racial, ethnic, gender, and geographic diversity of the U.S.”

In that, they appear to have succeeded by adding members with specific health equity expertise.

They include Valarie Blue Bird Jernigan, a professor of rural health at Oklahoma State and executive director of the Center for Indigenous Health Research and Policy; Angela Odoms-Young, an associate professor at Cornell in the Division of Nutritional Sciences whose research looks at “social and structural determinants of dietary behaviors and related health outcomes in low-income populations and black, Indigenous and people of color”; and Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine physician-scientist, educator, and policymaker at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School who also is equity director at the hospital’s Endocrine Division.

The appointment of those members is “definitely a big step forward,” said Jessi Silverman, senior policy associate at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “I can't say for certain whether … we'll be able to have expertise on every single question that might come up. But it's definitely a big improvement.”

In addition, according to HHS and USDA, the committee will review the scientific questions with health equity in mind “to ensure that the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans is inclusive of people from diverse racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds.”

That means exploring “whether additional examples of healthy dietary patterns should be developed and proposed based on population norms, preferences, and needs of the diverse individuals and cultural foodways within the U.S. population,” the agencies said.

“HHS and USDA will also start examining best practices for adding systems approaches (considering the multiple factors that influence individuals’ dietary patterns) to the rigorous evidence review process used for developing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans to ensure they reflect the highest scientific integrity and contain information adaptable for public health and consumer use.”

“I think it should be more than a lens,” said Mary Story, director of Healthy Eating Research, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The committee “really needs to look deeply at the question of, especially, racial inequity.”

“I'd like to see questions that really are not just looking at it within a health equity lens, but really look at what has been working, what do we know is effective, because one size doesn't fit all without intervention,” she said. “So if you look, for example, at African-Americans or Latinx, what does seem to really be affecting those populations?”

Silverman said there has been a “lack of clarity” so far on how health equity will be incorporated in the scientific review, but he noted that the DGAC has been charged with examining “whether additional examples of healthy dietary patterns should be developed based on based on the preferences of diverse cultures.”

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse by clicking on our link!

“For example, should there be less reliance on dairy in a particular dietary pattern because certain demographics have high incidence of lactose intolerance,” she added.

In comments on the proposed scientific questions, CSPI recommended that the next guidelines reincorporate language from the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans that recommended supporing "healthy eating patterns for all,” which “was followed by specific policy, systems, and environmental change strategies to make it easier for people to eat the recommended eating pattern.”

“Many people in the United States face profound structural and socioeconomic barriers that place a healthy diet out of reach,” CSPI said. “Given the Biden administration’s unprecedented commitment to nutrition security and health equity, it is an opportune time to reincorporate (policy, systems and environmental) strategies into the DGA, building on the content from 2015 with much greater attention to health equity.”

The issue of dairy product consumption is likely to be discussed, said Geri Henchy, director of nutrition policy at the Food Research and Action Center.

Geri Henchy, FRAC

Geri Henchy, FRAC“Part of what I think they're going to be looking at is that, for example, there’s a higher proportion of some groups of American adults who can't digest cow's milk,” she said. “They might need Lactaid, or they might want some other kind of (non-dairy) milk.”

The International Dairy Foods Association, perhaps anticipating a discussion on dairy, said in comments on the proposed scientific questions for the DGAC that the guidelines should include, as they did in the 2020-2025 version, “specific language about other dairy options for individuals who have lactose intolerance, such as reduced-lactose milk, yogurt, and cheese.”

“People who believe they have lactose intolerance often choose to stop consuming dairy foods altogether based on lack of accurate information, misinformation, or lack of access to healthcare or nutrition professionals who could advise them on reduced lactose options,” IDFA said.

The National Milk Producers Federation called on HHS and USDA to analyze data on the incidence of lactose intolerance, "using scientific measurements in addition to self-reporting."

"Self-reported lactose intolerance may be considerably in excess of rates found when accurate diagnostic measures are used, suggesting a possible need for more consumer education on this topic, since avoiding dairy foods because of perceived lactose intolerance may inadvertently deprive people of dairy’s unique nutrient package," NMPF said in comments on the proposed scientific questions.

"Rates of lactose intolerance are higher in communities of color while the incidence of some conditions that may be favorably affected by dairy consumption, such as hypertension, is also higher," NMPF said. "This paradox suggests the need for better education on the availability of low-lactose and lactose-free dairy foods."

In August, a coalition of groups including the National Urban League called on USDA’s Equity Commission to recommend “a proportional reimbursement to public schools for soy milk.” They said that up to 80% percent of Black and Latino people, up to 95% of Asians, and more than 80% of Indigenous Americans cannot digest lactose without adverse effects. In contrast, only about 15% of people of European descent are lactose-intolerant.

Henchy said the committee will be challenged by a lack of research on health equity and diet. “For a long time, people didn't like to say anything about race or racism. And they wouldn't be direct if they did. Now, people will be direct and say, well, there's structural racism. And if there's structural racism, it's going to have an impact on people's nutrition and health and their food security. And we have to address it. We can't be silent about it. And it matters for the dietary guidelines.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.