Anaerobic digesters that can turn manure gas into biomethane for the transportation sector and other industrial uses are a key part of the dairy industry’s strategy to get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

And business is booming, propelled in large part by support in California, which spent about $200 million between 2014 and 2020 to fund digester projects. The state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard program also is driving digester construction by rewarding biogas production with credits that can be sold to companies so they can continue to emit GHGs.

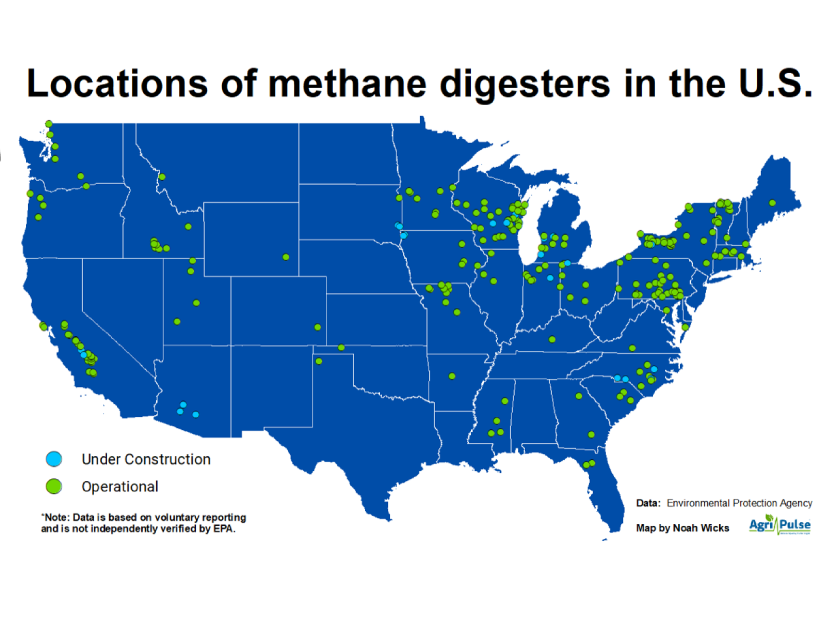

EPA data show 44 of the 355 digesters at farms nationwide became operational last year, with 36 of those in California alone.

On Monday, the White House issued a statement with details about its efforts to reduce emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with much more warming potential than carbon dioxide, but one that also only lives in the atmosphere for about 12 years. USDA’s Rural Development mission area spent $200 million on digester projects in 2021, the White House said.

“The potential for growth of the U.S. biogas industry is huge,” says the American Biogas Council, estimating 8,574 dairy, poultry and swine farms could support new systems.

Newtrient, a dairy industry-funded research group founded by 12 cooperatives, says "anaerobic digestion has been one critical solution by converting manure carbon to methane for energy production as electricity, heat, and renewable natural gas. This technology provides the ability to capture emissions before entering the atmosphere while reducing the need for fossil fuels.”

The group’s statement came in comments submitted in December to the California Air Resources Board in connection with a workshop on potential changes to the LCFS.

Although dairy farms so far dominate the digester landscape, the pork industry also is getting into the game. Kraig Westerbeek, vice president of Smithfield Renewables for Smithfield Foods, says that “along with our JV Partners, we have completed construction and are currently operating several of the largest manure-to-energy projects in the U.S.”

More than 100 Smithfield digesters “are producing and capturing biogas from nearly 100% of our company-owned finishing farms in Utah and Missouri,” Westerbeek said in an email to Agri-Pulse. “We currently have projects under construction in Arizona, North Carolina, and Virginia, and we are considering expanding into other states.”

In all, he says, “these opportunities across our U.S. operations could produce up to 5.3 million dekatherms of [renewable natural gas], which is equivalent to removing 630,000 vehicles from the road.”

Not everyone, however, is thrilled about the surge in digesters. Four groups recently petitioned CARB to exclude biogas from dairy and swine operations as approved pathways in the LCFS, claiming that CARB has not adequately considered th e full lifecycle costs of the process.

e full lifecycle costs of the process.

“The LCFS fails to include the full quantity of associated upstream and downstream greenhouse gas emissions, leading to an exaggerated negative carbon intensity value and a corresponding inflation of LCFS credit prices for factory farm gas,” the petition filed by Food & Water Watch, the Association of Irritated Residents (AIR), Leadership Counsel for Justice & Accountability, and Animal Legal Defense Fund says.

The result, the groups say, is that California is encouraging the expansion and consolidation of existing dairy farms, allowing pollution to increase both at those operations and at facilities that have purchased LCFS credits.

Tyler Lobdell, an attorney with Food & Water Watch, says CARB’s lifecycle analysis for ethanol under the LCFS “includes the growing of the corn,” but the LCA for biomethane produced by swine or dairy digesters treats the manure lagoon “as though it magically appeared there, and doesn't really look anywhere outside of that.”

“Digesters … entrench the very practice that causes those methane emissions,” without addressing greenhouse gases from the rest of the operation, Lobdell says, including the feed grown for the animals as well as their enteric emissions, and often, the use of the manure left over from the anaerobic digestion process.

Mark Stoermann, COO of Newtrient, says emissions from dairy production and processing “have already been captured in the lifecycle analysis of dairy products.”

Stoermann says that taking that into account, the LCA for biomethane only looks at manure management, resulting in negative Carbon Intensity scores that fetch higher LCFS credit prices.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

In its comments to CARB, Newtrient said, “CARB did consider that there are feed production and enteric emissions from dairy operations, but that these were outside the boundary of the livestock protocol because they are part of the natural emissions from the dairy operation, which are covered under the carbon footprint of the milk and meat produ ced.”

ced.”

To Lobdell, the comments sound like an acknowledgment that CARB “treats manure lagoons as naturally and spontaneously occurring, without regard to the factory farm that fills the lagoon with liquid animal waste and other pollutants in the first place.”

CARB denied the petition Jan. 26 but said it would hold a public workshop “in the coming weeks to delve into claims regarding the LCFS program and its impact on the dairy sector. At a minimum, it is trying to understand the economic trends in the sector that could be attributed to the LCFS program specifically.”

Stoermann rejects the notion that the LCFS is spurring expansion or consolidation of dairy operations. “Pressures driving dairies to become larger are more related to milk pricing and milk markets than they are to manure,” he said.

Dairies “have been consolidating for years,” he says. “And it's got more to do with the economics of the dairy industry.”

But Lobdell says FWW and the coalition behind the petition have identified dairy and swine operations that have either expanded after installing a digester or plan to do so.

Costs of installing a digester vary widely depending on the size of the operation, but the capital cost for complete digester systems ranges from $1,000 to $2,000 per cow depending on herd size, according to the Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Community. The cost of operating the digester, according to a 2018 article, was about $588,000 per year for a 2,000-cow dairy, or $294 per cow.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com

![Steve headshot 250x200[1]](http://www.agri-pulse.com/ext/resources/Headshots/Staff-Photos/thumb/Steve_Headshot_250x200[1].JPG?1738947158)