Northern California reservoirs are hitting their lowest levels in history and a third year of drought is growing more likely. This leaves state officials with difficult decisions ahead, as they spend the next two months ironing out a plan to preserve the bare minimum of water needed for basic human health and safety, which they already acknowledge may not work.

Rather than planning across historical 80-year precipitation averages, the starting point is now one of scarcity—to plan for the worst-case scenario and hope for relief.

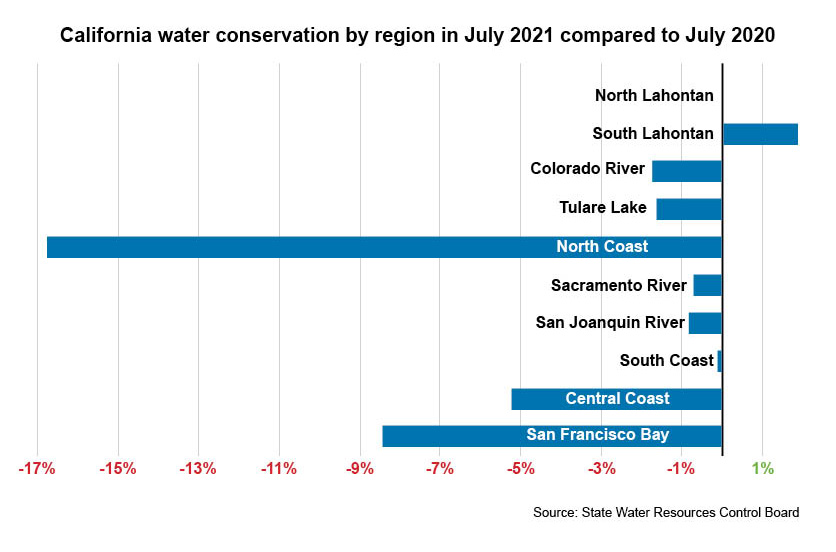

The latest data on water conservation show much more action is needed. Voluntary cutbacks in July amounted to less than 2% of additional water savings statewide, according to numbers released Tuesday. That is far below the 15% Gov. Gavin Newsom called for in July, though forthcoming data for August will serve as a better indicator of the public response.

The numbers show the North Coast region led the charge, with a 17% reduction in water use compared to the prior year—a result of mandatory curtailments for the Russian River watershed that started in June. At the other end of the spectrum, the South Coast region encompassing Los Angeles cut water use by just 0.1%, while users along the Colorado, Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers as well as the Tulare Lake region contributed less than 2% each in savings. The Central Coast, at 5%, topped the list for voluntary actions. The state has also maintained a 17% reduction in overall water use since the last drought.

“We're going to have to continue to deep dig in deeper,” said Joaquin Esquivel, chair of the State Water Resources Control Board, during a press conference Monday. “Conservation is a really critical tool.”

The administration is now narrowing its focus to two broad conservation targets. It would maintain at least the existing amount of storage into next summer, which is about two million acre-feet for Northern California reservoirs, assuming no new water is added through winter storms. If possible, the administration would like to more than double that number to meet the same level of carryover storage as the end of 2020, which was also a dry year. The department will put the plan in front of the water board in December, along with petitions for emergency regulatory changes reflecting actions in the plan.

Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth said this action puts water contractors south of the Delta “on notice” that they will likely receive no water allocations from the State Water Project (SWP) this year and that they should assess whether basic human needs can still be met. Settlement contractors for the San Joaquin tributaries, senior water right holders and other irrigators are included, signaling that farmers should plan for no water allocations from either project next year.

Outside of mandatory curtailments on the North Coast, the state initially fell short of Gov. Newsom's goal of 15% voluntary cutbacks, though that might change. Percentages stand for how much water was conserved. One region used more water, but made up for that in other ways.

She saw only “a slim likelihood” those contractors would have allocations next year, since the state would need to experience more than 140% of normal precipitation over the coming months, and it would have to come in the form of a warm weather system with torrential rain, rather than as snowpack.

Lake Oroville is facing a massive deficit and will not be able to deliver water again next year. Lake Shasta and Lake Folsom are critically low as well. The state expects to continue to use storage from New Melones Reservoir further south to pump into the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta to satisfy requirements for federal biological opinions and the state incidental take permit for the SWP.

Nemeth has received initial feedback from contractors showing they would be able to meet critical human needs through conservation efforts and water exchanges. Along with managing for the environment and drinking water, the state and federal water projects will continue to push freshwater into the Delta to keep salinity at bay, which may involve installing more rock barriers.

“It takes a significant amount of water just to maintain the salinity barrier,” said U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Regional Director Ernest Conant, during a hearing Tuesday. “That’s an absolute priority of ours. We never want to lose control of salinity, because it takes a larger amount of water to get it back.”

Esquivel emphasized that the state is looking for local agencies to take the lead on water conservation, including for decisions over mandatory cutbacks. He said the state is releasing the water use data to help those agencies—as well as agriculture—be better decision makers in that process. But he acknowledged the state could step in to order mandatory reductions as well. Water board member Dorene D’Adamo said this could be an opportunity for San Joaquin River settlement contractors to present conservation ideas that the board could support.

The state’s drought plan will also include vulnerable communities that are not under SWP contracts but may have the capability to connect to the surface water.

Nemeth has been meeting with agricultural leaders to gain their perspectives and the topic of infrastructure investments has come up in those discussions, with mentions of the Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley and other collaborative efforts. She said the crisis “definitely does” suggest that more attention is needed for infrastructure spending, and she hoped it stimulates more conversation.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse West

“The fact that climate is now manifest in these water management decisions gives Californians and ag in the valley a new opportunity to press for infrastructure investments,” she said, adding that the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act is creating a better understanding of the investment gaps. “We finally have all the pieces in play. We know what kind of supplies we need in the valley.”

Nemeth pointed to the need for a better conveyance system to capture more water in the wet years. The SWP delivered the most water in history in 2017 and big water years like that will undoubtedly come again, she believes. The California Aqueduct, however, was designed for a certain amount of subsidence and the state has already exceeded that, inhibiting its ability to move and store large flows of water.

Voluntary settlement agreements over Bay-Delta flows and related habitat restoration projects could also play a role in the state’s new drought plan.

“One of the things that this year showed us is that there's so much uncertainty in the system,” said Nemeth. “It really, frankly, reinforces the fact that we need to do something—and we need to do something that's implementable right away—to deal with environmental flows and to establish a landscape-scale approach to habitat restoration.”

The administration had initially been pursuing a 15-year agreement, but with the uncertainty this year, an eight-year commitment is possible, she said.

During a meeting of the California Water Commission last week, Nemeth said farmers have also played a role in helping the department manage resources during dry times and for long-term needs, since farmers with 10,000 acres or more are now required to submit water management plans.

Nemeth hopes the department can more closely assess the watersheds that feed into the Central Valley to understand climate variability and climate risk.

“That information can help inform not only how we approach surface water, but more critically how that surface water is connected with our groundwater management plans and helps us understand what truly is available for recharge,” she said.

According to John Yarbrough, who oversees the SWP as assistant deputy director under Nemeth, the department has been working with other agencies to gather more data on watersheds and to adopt new modeling approaches to improve forecasting for next year. The department is also looking at ways to reverse pump water up the aqueduct for agencies to access their stored water and meet critical agricultural needs.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.