The ability to trace a head of lettuce, a piece of fruit or other type of food from the field or orchard to the fork could speed food safety investigations and potentially prevent illnesses and even deaths.

Many farms can already provide the tracking, but incompatible tracking systems and food industry gaps create critical weaknesses in the chain.

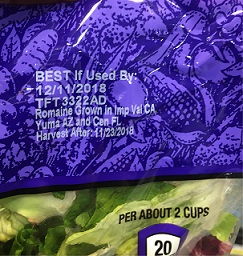

Case in point: After a three-month investigation, the Food and Drug Administration in February pinpointed the source of the 2018 E.coli outbreak in romaine lettuce to poorly sanitized water on a farm in Santa Barbara County, with more sources likely. The investigation drew in top U.S. and Canadian agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and multiple state ag and health authorities. After six weeks, the international coalition of researchers declared that the contamination likely came from one of the top counties in the nation for producing romaine lettuce.

California has made strides in food safety standards following major outbreaks in the past. National traceability initiatives have also gained a strong foothold in recent years. And in a state driven by the tech industry, data sharing tools like blockchain offer exciting possibilities for instant traceback. None of those were involved in this outbreak.

Yet this episode with romaine lettuce could be the needed linchpin for sweeping changes in supply chain management and regulation.

A shock to trust and finances

“From a grower perspective, it’s been frustrating because we have great traceability,” said a Monterey County romaine grower who asked not to be named. “At any given moment I could tell you exactly where a pack of romaine came from—what crew harvested it, when, what field location, what time of day, what truck number hauled it to the cooler.”

Our source pointed to restaurants and grocers in “the last mile” of the supply chain. Produce boxes are tracked to the store but then torn down, with individual packages put on shelves. It is typical for a month to go by before an illness is reported. By that point, the lettuce bag is long gone, along with a possible RFID tag on the box it came in and any tracking records.

Others have pointed criticism at the processor for combining romaine from multiple farms into the bags. The FDA also took heat for shutting down the entire industry, despite states like Alabama not producing romaine lettuce at the time.

It is still too early to quantify the economic impact from the voluntary recall. One recent study focusing on the 2018 romaine lettuce outbreak from Yuma, Ariz., estimated costs for fast food restaurants alone to be as high as $2 million. The 2006 E.coli outbreak in spinach, meanwhile, resulted in an immediate 20 percent loss of revenue for those retailers.

The story has been a touchy subject for victims. The E.coli O157:H7 contaminations led to at least 62 illnesses across 16 states and Washington, D.C.

Growers throughout the industry were blamed. In a statement, the Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement (LGMA) pointed out that - had that farm joined the voluntary agreement - it would have been subject to inspection at least five times per year. The organization said food retailers could have avoided this by sourcing from the agreement’s certified members, who represent 90 percent of the lettuce and leafy greens grown in the U.S. The agreement also preemptively satisfies the FDA’s new produce safety requirements under the Food Safety Modernization Act.

Blockchain is new. Traceability isn’t.

The LGMA began as a response to the 2006 spinach outbreak. Likewise, regulators, retailers, growers, processors and distributors have come back to the table to hash out new standards in the wake of the recent outbreak. One buzz phrase coming from this discussion has been blockchain technology.

The encryption tool is a digital ledger in which all points in a system get the same data at the same time, with no one entity holding the keys. This means that when a head of lettuce is tagged, bagged and tracked on its journey through the supply chain, all parties have access to that information the moment it is inputted. The platform can be a single, unified blockchain or a stream of chains across the supply chain, with many companies or even governments having their own blockchains.

The technology is already out there. Wyoming has welcomed a beef cattle test, turkeys even got the digital treatment for Thanksgiving and Driscoll’s, Walmart and IBM have been touting the success of a pilot project that may serve as a test case for larger grocers.

“What this did was enable Driscoll’s and Walmart to truly align,” said Brendan Solan, who leads supply chain platforms for Driscoll's, during a panel discussion at the USDA Agricultural Outlook Forum last month. “It gives us both the ability to see what’s going on in the supply chain.”

He said that, for the first time ever, they successfully tracked a tray from field to consumer. And now the companies want to leverage more IBM tech prowess to commercialize and scale this up to cover thousands or even millions of trays. As the leading grocery retailer by market share, Walmart would set an industry standard for blockchain. It already took a bold step in September when it declared that all of its direct suppliers must be “on the blockchain network” by Jan. 31, 2019. It’s unclear how many are currently on that network.

“What are we trying to do with blockchain? It’s simple: radical transparency,” said Robin Kalsbeek, the “value chain engineer” for the Sweetgreen restaurant chain, in the same panel discussion. “The possibilities are endless…. It’s in-field sensors, the farms, understanding when they harvest the food, how they grew it, what fertilizers they applied, the temperature within warehouses and trucks, all the way to a Sweetgreen bowl.”

Kalsbeek spoke at length about the many possibilities for customer feedback and integrated marketing.

Yet food safety experts caution that blockchain is just one tool and not a solution in itself to the issue of traceability. In fact, block chain could cause more problems if the software that a roaming harvest crew uses doesn’t talk to the software the grocery store implements, or if a grower is the only one in the chain to invest in the technology.

This is where standards like the Produce Traceability Initiative (PTI) are challenging institutional cultures and policies around food safety. If each company along the chain can ensure the same tracking standards, the technology won’t be an issue.

And that leads to more finger pointing as it revives old issues with data collection. Building a blockchain system for all companies across the supply chain takes careful negotiation over how much information is enough to still meet the traceback requirements without giving away valuable trade secrets.

An upgrade through crisis management

Ideally these outbreaks would never happen in the first place. But when they do, regulators and the industry need to know the source can be traced quickly and accurately. The technology and strategy to do so are already available.

After the 2006 outbreak, spinach groups set their own standards for traceability. It’s also a well-established practice for growers to track their produce for internal records, without calling it traceability. Food retailers, especially larger ones, have robust systems as well. But the technology and practices have not been standardized across the industry.

This is where PTI comes in. The initiative urges all companies involved in handling the 6 billion cases of annual U.S. produce to adopt one standardized system of labels, scanning and data collection. Since its inception, PTI has made significant strides in this adoption.

“When it comes to fresh produce, (retailers are) seeing maybe 50 to 70 percent of fresh produce cases labeled with the PTI label,” said Jennifer McEntire, the vice president of food safety and technology at United Fresh Produce Association.

She added that with leafy greens it’s “even higher.” McEntire admits that extra effort is involved in scanning each label for each step in the chain. But when it comes to the exorbitant costs of an outbreak—well into billions of dollars for the romaine lettuce incident—companies will be eager to invest in collecting that valuable tracking information.

“PTI is a really easy way to capture it,” she said. “But it comes down to making sure that all points in the supply chain are capturing it, or at least as close as you can get to where that consumer’s going to eat that food.”