(Editor’s note: This is the sixth installment in our seven-part in-depth editorial series where we look ahead at “Farm & Food 2040.” This story focuses on the expanding use of marketing and product differentiation available through food labels and how consumers digest that buffet of information.)

Point a smartphone at the “QR” (for “quick response”) symbol at the top of a box of General Mills Fiber One cereal (or any one of more than 36,000 products in a supermarket) and the phone displays far more information about the food inside than most consumers care to read.

It shows, for instance, the ingredients, the nutrition contents, the fact it contains wheat, a potential allergen, and includes ingredients produced with biotechnology, aka GMOs.

Although the system has limitations — it requires a smartphone and internet access, not always available to all consumers everywhere — it is the kind of technology many food industry and policy mavens expect to satisfy the demands of many customers for more information about the food they eat and how their diets might contribute to better health.

Such a mechanism also gives federal food regulators an option for prescribing how labels disclose information they require of food manufacturers and marketers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers it as one of several ways companies can comply with a rule requiring disclosure of bioengineered content in food beginning next year.

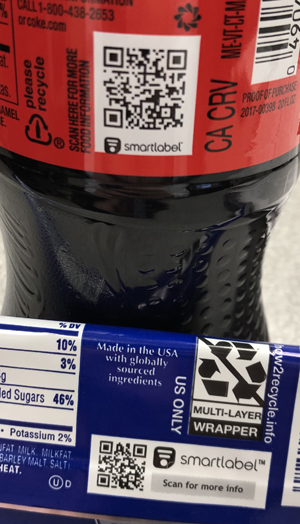

In three years since its launch by the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and Food Marketing Institute (FMI), the SmartLabel® system employing QR codes has built a database of 826 brands with more than 36,000 food, beverage, personal care, household and pet care products. Surveys show consumers would like to learn more about a product’s impact on the environment and adherence to social goals such as sustainability, its sponsors say.

A 2014 survey indicated 34 percent of consumers had read such codes at least once and its use is increasing year to year. Nevertheless, activists argue that the system discriminates against low-income, elderly and rural Americans who do not own smartphones, may not be able to afford service or may not understand how to use QR codes.

SmartLabel information can be seen on thousands of food items, including this bottle of soda and candy bar.

While consumers and their interest groups are likely to seek more, not less, information from manufacturers, industry will be challenged to translate an abundance of information into a format easily accessible to shoppers — how to include an increasing volume of information on a “limited supply of real estate.” Individual companies and their trade associations have begun efforts to do so, and experts anticipate that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will show renewed interest in developing a uniform, standardized format in the coming years.

If the previous generation’s experience provides a look into the future, it is possible for the next generation to envision a scheme that allows every product on a shelf to be linked directly to the farm or factory where it originates and the ingredients and attributes that make it unique.

Food labeling regulation is believed to have originated in the early 13th century when the king of England prescribed the ingredients of bread dough. In the United States, modern food regulation dates from 1862 when President Abraham Lincoln established USDA, which included authorities that moved to FDA in 1940.

Since then, both agencies have adopted and enforced a wide range of food labeling policies. USDA oversees labels for meat, poultry and eggs, organic crops and milk and dairy products. FDA regulates label claims for most packaged foods and fresh fruits and vegetables. The reach of food labeling has expanded at both agencies.

Meat, poultry and egg product labeling regulation is among USDA’s oldest responsibilities. It was authorized by the Meat Inspection Act of 1906, triggered by “The Jungle,” Upton Sinclair’s expose of unsanitary conditions in meat packing plants. Over the years, the “USDA Inspected” seal has become one of the most-recognized of all food labels.

The task has been lodged in several agencies, including the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Consumer and Marketing Service through the 1960s, in the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and briefly the Food Safety and Quality Service in the 1970s. It has been in the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) since the early 1980s.

In recent years, FSIS labeling authority has expanded to cover label claims the way food-producing animals are raised, including pasture-raised livestock, free-range poultry and eggs, or raised without hormones or antibiotics.

The Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) has assumed a greater share of USDA’s food labeling responsibility in recent years, first by implementing the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 and lately the national standard for bioengineered food labeling. While the new bioengineered standard requires compliance for most companies by January 2020, the regulation is caught up in controversy and opponents have threatened to block it in court.

“Unfortunately, instead of putting this issue behind us, these regulations will almost certainly lead to litigation, more state legislation and efforts to amend the federal law,” says George Kimbrell, legal director of the Center for Food Safety, which regularly sues USDA over biotechnology. “We will explore all legal avenues to ensure meaningful labeling.”

Despite more than two decades of experience, USDA enforcement of the organic label also creates ongoing disagreement. Critics say USDA has been lax, especially in the dairy sector, about enforcing its rigorous standards for pasture for milking herds.

George Kimbrell, CFS

In recent years, the two agencies have worked out arrangements that mostly avoid overlap. Their “Coordinated Framework,” adopted in 1986, divided responsibilities between them and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for regulation of agricultural biotechnology. Inasmuch as FDA treats products of biotech crops like those produced through other means, no labeling is required just because they are derived from bioengineering.

Just this month, USDA and FDA announced a framework agreement for regulation and labeling of cell-based meats and potentially other food products. FDA will regulate the cell collection and growth while USDA will regulate harvesting and labeling of the final product.

The announcement closes one chapter of the debate over how to treat cultured, or cell-based, products — meat grown from harvested animal cells rather than through the traditional harvesting process — but begins another as USDA and FDA must iron out details of the language.

FDA’s food labeling responsibilities have grown in parallel with USDA’s in the last century. The original Food and Drug Act of 1906 prohibited misleading labels on food sold in interstate commerce and the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 gave FDA the authority to set identity standards for food, which serve as the basis for regulation of many food label claims.

The biggest expansions of FDA label authority have come in the 1990 Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) and the 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). The former led to the ubiquitous “nutrition facts” panel on nearly all packaged foods, listing calories, contents and proportions of nutrients such as fats, sodium, sugar and carbohydrates. The latter is the basis of requirements for labeling of calories for many restaurants, still a work in progress.

How will food be labeled and regulated in the future?

If the recent past is an indicator, both FDA and USDA are likely to maintain or increase food labeling activities. The sweeping “FDA Nutrition Innovation Strategy” published a year ago lays the groundwork for modernizing label claims and updating the “nutrition facts” label and menu labeling requirements. It also suggests the possibility of developing a new icon for any food that meets a new definition of “healthy.”

Outgoing FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb

Outgoing FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb also launched an effort to update enforcement of the agency’s standards of identity. Such standards “help to ensure that consumers know ‘vanilla extract,’ for example, will always be made from vanilla beans and not artificial flavorings,” he said. “We’re on a fast track to take a fresh look at the labeling of products that are being positioned in the marketplace as substitutes for dairy products,” he added. “Implementing clear and transparent food labels and claims is an issue I’ve made a high priority.”

FDA’s request for comments attracted thousands of pleas from dairy farmers, led by the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF), for a ban on labels of plant-based or nut-based products — almond milk or soy cheese, for example. Fans and marketers of substitute products countered. The San Francisco-based Plant Based Foods Association (PBFA) told FDA that “most people, at least 74 percent, are in support of using the term ‘milk’ on the label of plant-based milks.”

Dairy products may not be alone in FDA’s new approach to standards of identity. The emergence of “cauliflower rice,” which is not actually rice but is cauliflower processed into rice-like morsels and packaged, has drawn the attention of rice producers and processors. The grocery chain Trader Joe’s may have defused the controversy, labeling the product “riced cauliflower.”

FDA is likely to continue to feel pressure to define the term “natural” on food labels and product names. Reaching a common definition “would be a big assist to the food industry,” says Michael J. O’Flaherty, an attorney at Olsson Frank Weeda Terman Matz in Washington, citing a proliferation of legal challenges to the use of the term on a variety of foods. “FDA has been working on that as long as I’ve been practicing law,” he adds — beginning in 1987.

“The rules evolve with the science,” O’Flaherty says. “That’s a trend that’s likely to continue.” With new tools, such as QR codes, “I see the possibility of a lot more voluntary information to be conveyed.” One example may be food traceability. In the event of a recall, “new technology might provide a way to label or include in a QR code where the product came from,” he says.

FDA’s new nutrition innovation strategy may provide an opening for a “low carbohydrate” food label that currently is not allowed, O’Flaherty observes. Changing the legal landscape would entail petitioning FDA to promulgate a regulation defining “low-carb” and possibly other claims about the total carbohydrate content of a food. FDA’s present regulations were promulgated in the early 1990s “and are a bit dated,” he opines.

A potential signpost on the road to the future of food labeling lies in the current “laundry list of labeling requirements” facing food retailers, Stephanie Harris, chief regulatory officer at FMI, says in a January 2019 blog post. “These labeling requirements include product identity information … (and) also varying types of labeling needs for food products depending on whether they are ‘packaged’ or ‘unpackaged’.” She noted that even imported fresh fruit such as the banana is subject to country-of-origin labeling requirements.

Stephanie Harris, FMI

The “laundry list” of consumer hopes for label information might include, depending on who is composing the list, a food’s country (or even domestic location) of origin, whether it follows certain “fair trade” characteristics, whether it was raised without pesticides or hormones, and whether it meets anticipated “natural,” “local” or “sustainable” expectations.

Manufacturers are responding to customer pressure for labels to clarify when a perishable food is no longer safe to eat. Since GMA and FMI launched a voluntary program in 2017, some 87 percent of products now carry “best if used by” or “use by” language.

Although odds appear small, USDA also may be able to dust off its old country-of-origin (COOL) label regulations for red meat. The grassroots producer group R-CALF USA late last year urged President Trump to issue an executive order to bring back mandatory origin labels for beef that’s consistent with his “Buy American Hire American” executive order. COOL was in force from 2013 to 2015 when Congress, reacting to pressure from interests affected by World Trade Organization (WTO) rulings finding COOL violated its agreements, repealed the scheme.

State and local food labeling laws and regulations also will bear watching. San Francisco is facing legal scrutiny for a 2015 ordinance that required health warnings that beverages with added sugars “contributes to obesity, diabetes and tooth decay.” A federal appeals court has ruled that the requirement probably violates the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Several state legislatures, unwilling to wait for FDA-USDA regulation of cultured meat substitutes, have passed or are considering bills sought by livestock producer constituents to ban the use of meat-like terms on labels of those or plant-based meat substitutes. Some have ended up facing legal challenges from alternative product manufacturers. A federal court in Missouri is considering a proposed settlement in a suit by the makers of Tofurky and the Good Food Institute (GFI), an advocacy group, against a state law that would ban labels with terms such as “burger,” “sausage,” and “hot dogs” from plant-based foods. Mississippi, South Dakota and Washington have similar bills.

One way to consider the future of food labels is to see how the last three decades of federal food labeling regulation have played out. USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) has evaluated the impact of labels that have been inaugurated in recent decades. Beyond Nutrition and Organic Labels — 30 Years of Experience With Intervening in Food Labels uses case studies of five food labels to show the economic effects and tradeoffs in setting standards and verifying claims.

The report, by a team of economists, compares five food labels — nutrition labeling, the USDA organic seal, meat and poultry products raised without antibiotics, the voluntary non-GMO product label and the now-lapsed country-of-origin label for beef and pork. They conclude many consumers find the information too complex to use.

The authors give high marks to FDA’s “nutrition facts” label on most food packages for providing information that most consumers treat as credible and truthful but note that many ignore. By contrast, it finds USDA-approved claims for animals raised without antibiotics gave credibility to competing labels but, because private firms independently defined what the claim means, the label has not ensured that consumers understood differences in products. Because USDA has limited resources to enforce animal-raising claims, private organizations have been the chief impetus for penalizing violations by going to court.

Effects on trade have been mixed. Setting a national organic standard ended variance among state standards and gave the organic sector more access to interstate and international markets, increasing sales, ERS finds, but the WTO found COOL acted as a barrier to trade in meat.

The report suggests smartphone apps offer a new way to convey information that can’t fit on a food label. “Many consumer and environmental groups, retailers and other organizations have developed apps that provide information to users on health and nutrition, social issues and environment attributes,” it says. “Apps are largely uncertified and unpoliced, which means they are of dubious quality.”

ERS points out the fundamental tradeoffs in how information is presented to consumers. “If it is presented simply, then important nuance or complexity may be missed. On the other hand, if standards and labels attempt to convey complexity, then consumers may just be confused.” It says policymakers need to consider such tradeoffs when developing new process-based labels.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com