WASHINGTON, Oct. 25, 2017 -- A group of sociologists and analysts tried to draw a picture of rural poverty in America at a forum in Washington last week and explain why economic and social conditions are worsening in the hinterlands while most urban folks have left the Great Recession behind.

The panel, gathered by the American Enterprise Institute, described U.S. rural poverty as a mosaic that’s becoming increasingly diverse in location and racial and ethnic makeup even while the total share of rural residents below the poverty line has swelled to about 17 percent in recent years, near its last peak level in the 1980s.

James Ziliak, director of the Center for Poverty Research at the University of Kentucky, pointed to the drought of human capital as the chief rural economic weakness.

James Ziliak, University of Kentucky

“The missing market in rural America is the demand for and supply of highly skilled labor,” he said. Research shows that 60 percent of the gap between the average income of urban and rural workers is attributed to human capital (skill, experience and total capabilities of workers). Another 15 percent of the gap, he said, is owed to “urbanicity” – the superior economic infrastructure and services that metropolitan areas offer versus rural areas.

The panel spoke of the political realities and social ills that helped prompt their forum in the first place.

“Rural America sort of stepped up this last election and told us how they feel,” said Daniel Lichter, a Cornell University sociology professor and policy analyst who grew up in rural South Dakota, referring to the strong rural vote for President Trump that surprised pollsters.

Dottie Rosenbaum, an expert on child nutrition programs with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, asked her fellow panelists how they view news reports on the opioid epidemic, which is being felt especially hard in rural America.

“It’s real,” Ziliak replied, “and it’s due primarily to the lack of economic opportunity ... lost jobs,” heavily hitting the 45-to-60 age group and contributing to rising rates of alcoholism, drug abuse and suicides in economically depressed rural areas.

Lichter agreed. “If you look at the landscape of despair (in rural America), this is a white, working class phenomenon, clearly linked to economic problems.” He also described “key dimensions” of rural poverty:

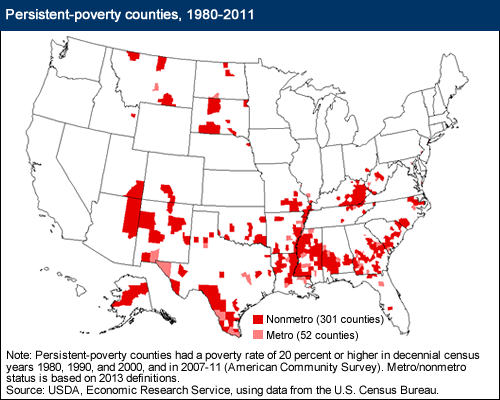

• Regional concentration. Clumps of poor Hispanics in the desert Southwest and along the Texas border; blacks in the Mississippi Delta region and Southeast interior; American Indians in reservations across the West; poor whites in Appalachia.

• Persistence. Poverty in the regions noted above has been chronic since President Lyndon Johnson launched his War on Poverty in 1967, with about the same 11 percent of all U.S. counties, nearly all rural, remaining in poverty for half a century (see map).

• Working poor. Traditionally, rural people below the poverty line more typically had jobs than in urban areas, but that difference has evaporated, even though rural single moms still have comparatively high rates of employment.

• Family changes. The fastest change to the profile of American families is in rural populations, where the incidence of unmarried, cohabiting parents and single mothers is rising much faster in rural than in urban areas.

• Immigration. The traditional concentration of new arrivals along the U.S. southern border, especially the Southwest, changed rapidly after about 1990, and the nation has had “a tremendous dispersal of immigrants and minorities” coast to coast.

The best solution to rural poverty? “Invest in children,” beginning with childhood development programs, Ziliak argued.

The panelists agreed that improving schools poses a big hurdle for financially depressed school districts with depleted tax bases. But Lichter insisted, “We’ve got to somehow bring our schools up to speed.”

#30

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com