The 2018 farm bill isn’t due to expire until 2023, but there is a growing possibility that Congress could revisit the law as soon as next year either to deal with the slumping farm economy or to address climate change.

Two of the three Republicans running for the top GOP seat on the House Agriculture Committee go so far as to say Congress should consider writing a new farm bill next year because of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis and economists’ gloomy long-term forecasts for commodity markets.

The National Farmers Union, a group whose populist leanings mean that it will likely become more influential on farm policy if Democrats win the White House and both chambers of Congress, is working on developing supply-management options as a way to boost commodity prices.

Meanwhile, a sweeping climate plan released by House Democrats June 30 calls for a massive expansion and rewrite of farm bill conservation programs. Former Vice President Joe Biden, the Democratic Party's presumptive presidential nominee, has separately proposed a major increase in conservation spending if he wins the White House.

One of the three candidates for the top GOP slot on House Ag, Arkansas Rep. Rick Crawford, told Agri-Pulse that farm bills should probably be written every two to three years, not five, much like Congress reauthorizes defense programs every year to reflect changing national security needs.

Agricultural “market conditions can change dramatically in the course of a year, and certainly in the course of five years,” Crawford said.

“There have been so many different things that have dramatically affected rural America and production agriculture,” he continued. “I think we're almost going to have to revisit (the farm bill) and address policy in a more timely fashion.”

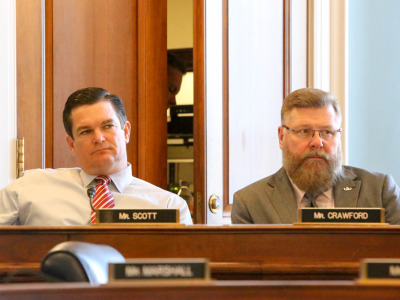

Rep. Austin Scott, R-Ga., (left) and Rep. Rick Crawford, R-Ark., (right) listen to the proceedings of a House Agriculture Committee hearing in March.

Net cash farm income is projected to drop 15% to $102 billion this year, even with the $16 billion in coronavirus relief payments that USDA is now distributing, and then fall to $95 billion in 2021, according to a forecast released last month by the University of Missouri’s Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute, which analyzes policy issues for Congress and federal agencies.

A second candidate for the House committee post, Georgia Rep. Austin Scott, also thinks a new farm bill is needed and says one “interesting” idea is to return to an "old set-aside-type program where you took more of the acreage out of production, where you actually reduce the supply, and then hopefully you get to a price level that is profitable.”

He says that could be done through expanding the existing Conservation Reserve Program, which was created in the 1980s in part to reduce production. Supply management was a key feature of the Depression-era farm programs that Congress dismantled in 1996, but there now appears to be at least some bipartisan interest in set-asides.

A COVID-19 aid package that passed the Democratic-controlled House in May, the HEROES Act, included a provision to expand a pilot program in the 2018 farm bill, the Soil Health and Income Protection Program, from 50,000 acres to 5 million acres at an estimated cost of $1 billion. Farmers could enroll land in the expanded SHIPP for three years for a payment of $70 an acre. SHIPP was originally proposed by South Dakota Sen. John Thune, now the Senate GOP whip.

Rob Larew, president of the National Farmers Union and a former top aide to House Ag Chairman Collin Peterson, D-Minn., told Agri-Pulse that his organization’s board recently directed staff to develop supply-management options for the group to consider.

“The measures that Congress has already taken to address the impact of the pandemic have been important, but we know that they are not going to be enough,” he said. "So I think it’s reasonable and appropriate to be thinking bigger and more systematically (about) how we should structure support for farmers.”

The NFU has advocated supply management for dairy for some time, and now is looking at the possibility for grain producers as well, he said. “You cannot keep farming year after year at these prices, so we have to come up with solutions, and that's what we we've been challenged to do,” he said.

But supply management proposals, including attempts to expand CRP significantly, nearly always draw strong opposition from grain buyers. And some prominent agricultural economists are warning that government attempts to reduce production could backfire on U.S. farmers without having a major impact on the prices they get for their crops.

The reason: Foreign production of major commodities such as grain, soybeans and cotton has increased so dramatically over the past couple of decades that reductions in U.S. acreage won’t necessarily drive up market prices significantly. U.S. acreage cuts instead would encourage foreign competitors to increase production and seize market share from American farmers, according to an analysis by economists from The Ohio State University and the University of Illinois.

Rob Larew, NFU

The last time Washington acted to reduce production significantly — in the 1990s — U.S. farmers produced 49% of the world’s soybeans and 40% of the world’s corn and accounted for 70% of global soybean exports and 72% of global corn exports.

Now, U.S. farmers account for just 34% of world soybean and corn production. The U.S. share of global exports has dropped to 37% for soybeans and 35% for corn.

The U.S. share of cotton and wheat production also has dropped significantly.

America’s shrinking market power means that retiring U.S. acreage “will likely lead to a quick loss in U.S. share of world exports and production,” the economists write. “Moreover, what may have been enacted as a temporary reduction in U.S. output has the real potential to become a permanent reduction.”

The study’s lead author, Carl Zulauf of Ohio State, told Agri-Pulse that Brazil’s increased ability to double-crop corn is the “real game changer” when it comes to weakening U.S. market power. That “has given South American the ability to respond within the U.S. crop year to any cuts in U.S. production of the two crops that account for over one-half of U.S. principal crop acres,” Zulauf said.

Zulauf noted, however, that Congress could decide to permanently reduce production for environmental reasons, something the House Democrats’ climate plan could do. The plan cited a bill introduced by Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., that would increase CRP to 40 million acres by 2030. Some 22 million acres are now enrolled.

Senate Agriculture Committee Chairman Pat Roberts, who is not running for re-election this year, thinks reopening the farm bill would be a mistake given the hyper-partisan environment on Capitol Hill. “Be careful what you wish for,” the Kansas Republican said. “I think opening up the farm bill, given the politics on steroids right now, would be a very difficult task.”

Barry Flinchbaugh, an economist at Kansas State University who has advised lawmakers on numerous farm bills, agrees with lawmakers such as Crawford and Scott that the 2018 version has proven inadequate, but he worries that farmers might wind up worse off.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse or Agri-Pulse West by clicking here.

“Every time we’ve played with a farm bill, halfway through the bill or partway through the bill, we caused farmers problems,” Flinchbaugh told Agri-Pulse.

Flinchbaugh said USDA should instead continue providing ad hoc payments like those provided under the Market Facilitation Program and Coronavirus Food Assistance Program.

The third challenger for the top GOP position on House Ag, Pennsylvania Rep. Glenn Thompson, said he would be reluctant to reopen the farm bill without public hearings or if Democrats control the House.

“Although rural America faced significant challenges in 2018 and average farm income was down nationwide, COVID-19 has presented new and unique difficulties for the entire agricultural sector. This does not reflect a failure of the farm safety net, but rather is an issue of appropriations where programs have required additional funding,” he said in a statement.

A Democratic-controlled House would use the farm bill “to make pie-in-the-sky environmental policy that will not be good for farmers, producers, American families or the economy,” he said.

Ben Nuelle contributed to this report.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.