WASHINGTON, Feb. 10, 2016 - Gigantic market opportunities in the production of organic livestock feed and forage await both American organic producers ready to expand and conventional ones willing to try organic farming.

Why? The robust growth of the organic meat, eggs and dairy markets has left U.S. organic feed production far, far short of the needs of the animals producing those foods. A snapshot: U.S. retail sales of all organic foods swelled by 66 percent from 2008 through 2014, Organic Trade Association surveys indicate. Plus, OTA projects growth will average 14 percent annually for the next three years. However, U.S. farmers aren’t accommodating that growth: total U.S. organic acreage for grains and oilseeds commonly used to make feed rose less than 2 percent from 2008 to 2014; for organic hay and haylage, just 4 percent, USDA Census of Agriculture data shows.

Instead, farmers abroad are responding to the soaring feed demands of U.S. organic livestock operations. Penn State University researchers reported last year, for example, that imports of organic soybeans (mostly from China, Canada, Ukraine and Argentina) shot up from $42 million in 2011 to $184 million in 2014, while organic corn (largely from Romania, Turkey, Netherlands and Canada) jumped from zero to $36 million in the same period.

“American farmers are missing out on an opportunity, particularly around feed and feed grains,” says Nate Lewis, crop and livestock specialist for the Organic Trade Association. “We are a corn- and soybean-exporting country, but we are importing a large percentage of the crops needed for feed on organic farms.”

Changing that situation won’t be quick and easy, Lewis says. Organic livestock farms “would like to source their feed closer to home.” But, he says, “overcoming the barriers is fairly complicated” and will require infrastructure changes. Local elevators and U.S. farmers, for example, will have to expand space segregated for organic feed storage, and feed mills wanting organic feed must first meet stringent USDA rules to avoid blending with even traces of conventional grains.

For farmers wanting to consider transitioning acreage to organic field crops, a ton of resources are available, though the path to do so is complex. (See our December article.) It’s more than worthwhile to get some mentoring from other organic producers, including local or regional organic farming groups such as the Midwest Organic & Sustainable Education Service. Also, start by checking out the Organic Transition Planner, produced through USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). It covers the gamut of transitioning: advice on key concepts, detailed worksheets covering farm operations, marketing, hiring questions, finances, etc. All of the planner’s electronic spreadsheets and worksheets are available here.

Meanwhile, projecting a good profit is a hurdle for all who grow such crops. Organic grain and oilseed prices have dimmed with the strengthened U.S. dollar, which accelerates the flow of imports as it pulls down domestic market prices, despite the strong domestic demand. Heath Dewey, who tracks organic grain and soybean prices for USDA Market News, said he watched cheaper imports, including Canadian organic grain coming south, erode U.S. prices. Feed-quality organic corn and soybeans are both averaging about $4 a bushel less than a year ago.

Nonetheless, prices for organic corn, at $8.50-$10 per bushel, and organic soybeans, averaging $22 a bushel, are both running about 150 percent more than the conventional market.

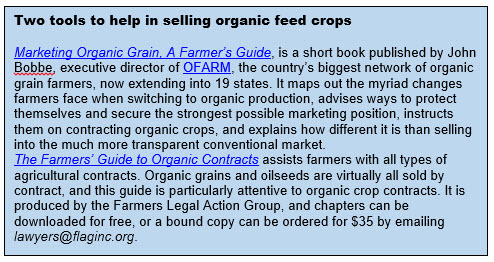

John Bobbe, a long-time cooperative marketing advocate who

heads OFARM (see text box), says getting a marketer’s services usually spells

higher contract prices. Contracting demands a lot of a producer’s time, often

more than he can devote to it. Meanwhile, Bobbe says, hiring an agent, whether

via a co-op, marketing club or another way, “is having someone who is in the

organic markets every day on your side of the bargaining table.” Besides that,

he points out, “volume talks when it comes to contract negotiations,” and

co-ops, which are legally allowed to bargain collectively, “are in a much

better position to negotiate terms of contracts favorable to their members than

are individuals.”

John Bobbe, a long-time cooperative marketing advocate who

heads OFARM (see text box), says getting a marketer’s services usually spells

higher contract prices. Contracting demands a lot of a producer’s time, often

more than he can devote to it. Meanwhile, Bobbe says, hiring an agent, whether

via a co-op, marketing club or another way, “is having someone who is in the

organic markets every day on your side of the bargaining table.” Besides that,

he points out, “volume talks when it comes to contract negotiations,” and

co-ops, which are legally allowed to bargain collectively, “are in a much

better position to negotiate terms of contracts favorable to their members than

are individuals.”

Bobbe advises that “nothing is ever done in organic graining marketing without some sort of contract,” and, “in business, you get what you negotiate, not what you deserve.”

OTA’s Lewis says hiring a marketer “is not the way every farmer wants to interact with the market.” Still, the trouble with the organic market for field crops is prices are set between a farmer and a buyer, he says, and that leaves pricing “fairly opaque,” unlike that for conventional crops, where market prices are posted daily. “So it’s really challenging for [organic] farmers to learn where those markets are,” he says.

Lewis says he has observed that “farmers who do have a marketer seem to access the markets more fluidly.” Those who don’t “seem to be less aware of the marketing opportunities that are out there.”

They tend to stick with the same buyers year after year instead of looking for a better deal. Also, “they may not know what the markets are for their rotation crops. And I think that is where a marketer might really come in handy.”

#30

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com