WASHINGTON, July 28, 2014 – If a recent poll is any indication, Sen. Kay Hagan appears to be holding onto a small lead in a hotly-contested race that could determine whether Democrats retain their control of the U.S. Senate next year.

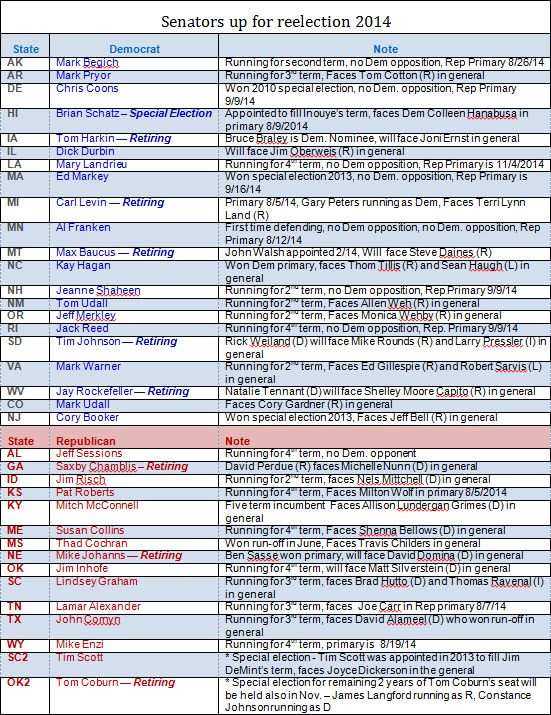

There are 36 Senate seats in play this year and 21 are held by Democrats like Hagan with 15 in the hands of the GOP. If Republicans hold all of their own and pick up six additional seats, they can gain control of the Senate, setting the stage for Republican control of both chambers during the last two years of Barack Obama’s presidency.

In North Carolina, Hagan leads her Republican challenger, state House Speaker Thom Tillis, by 7 percentage points, according to a July 17-20 survey by Public Policy Polling, with a margin of error of plus or minus three points.

However, polls offer just a snapshot of public sentiment at any given time. In political terms, it’s still a long way until the November elections, and pundits and political operatives are watching and videotaping almost every move – waiting for something akin to “a Todd Akin moment,” where members of the Missouri Senate hopeful’s own party faced the troubling reality of disavowing their own candidate because of some of his comments.

At the same time, Democrats and Republicans are ramping up their investments in this heated political battle. Since Jan. 1, 2013, Hagan’s campaign has taken in more than $14 million, leaving her with over $8.7 million in cash as of June 30. During the same time period, the Tillis campaign collected over $4.7 million and, after a contested primary, he has about $1.5 million in the bank.

But those numbers pale compared to some of the spending by outside groups to influence the race -- money that often don’t have to be reported to the Federal Election Commission. Republicans say such groups have spent $11.1 million so far against Tillis, while Democrats estimate outside groups have spent $18 million against Hagan, according to a McClatchy analysis.

With donation numbers like that, it seems an unsurmountable task for the state’s approximately 50,000 farmers to influence this Senate race. Even if all of them donated dollars and turned out to vote, could farmers possibly make a difference in a state with over 9.7 million residents?

“Not really, when you consider that there are fewer and fewer farmers in our state,” says Ferrel Guillory, the director of the Program on Public Life and journalism professor at the University of North Carolina. “But that’s not the end of the story. Two other important changes have happened.”

Guillory says the old southern democratic political construct, where the “elite courthouse crowd who once fought to keep segregation but later gathered support for Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and New Deal programs, is all gone. They’ve been replaced by Republicans.”

While some primarily black southern counties will go to Democrats, rural white voters in the South are overwhelmingly Republican, Guillory said.

“As a result, they can form coalitions with business and professional people and control much of the South.

“That’s the big historical change. The center of gravity for Democrats has moved to the cities.”

Secondly, Guillory says that, within the American psyche, there is a feeling that “many of us have roots in farming or small towns.” It is not an experience shared by his children, but he says that many Baby Boomers still have that type of connection.

“So there is a psychological clout that exists, even as the economic and political clout has waned.”

The Senate sway

Kyle Kondik, managing editor for Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia Center for Politics, says that while there may be fewer rural districts in the U.S. House of Representatives, one thing that has not changed is that every state gets two senators.

“So states that are rural have more power than they would if Senate seats were handed out proportionally by population. That inherently gives agriculture and farmers a bigger say in policy than they otherwise would have.”

But Kondik also agrees that many voters have a “cultural identity” with farmers, providing them with influence that belies their actual numbers.

“The idea of being a farmer is kind of a cultural identity issue in the same way that, in a place like West Virginia, coal mining and coal is just part of the cultural identity of being a West Virginian. So someone in West Virginia may not actually work in a coal mine, but a lot of people there identify culturally with coal in a way that’s bigger than the actual industry.

“By the same token I would say there are a lot of people who aren’t farmers in say, Iowa or Nebraska or Kansas, but I think people who live there may kind of generically identify with agriculture as being perhaps a bigger employer than it actually is.”

For an example, Kondik points to the Iowa Senate race where Republican Joni Ernst is battling Democrat Rep. Bruce Braley for the seat held for the past 30 years by retiring Democrat Tom Harkin.

Even though farmers make up less than 5 percent of the Hawkeye state’s 3 million residents, agriculture is playing an incredibly important role in the campaign, albeit for reasons one would not normally expect.

In January, Braley spoke to a group of trial lawyers in Texas who were possible donors to his campaign. In a video posted online by America Rising, a GOP-aligned organization, the former trial lawyer tried to persuade his audience about how important it was for him to win the race and more generally, for Democrats to retain their majority in the U.S. Senate.

During the pitch, he told fellow trial lawyers that a GOP takeover of the Senate in November could turn the Judiciary Committee chair over to the Iowa’s popular senior statesmen, Senator Chuck Grassley. In a rather stunning political gaffe that seemed to paint all farmers as underachievers, he referred to Grassley as a “farmer from Iowa who never went to law school.”

Braley apologized, but the GOP is hitting him hard for delivering the Iowa equivalent to Mitt Romney’s infamous “47 percent” comment that was captured on tape during the 2012 presidential campaign and used by Democrats to make Romney appear to be critical of poor folks.

A GOP super PAC, Priorities for Iowa, has already inserted the comments into a $250,000 advertisement buy against Braley. The tagline of the spot: “Tell Bruce Braley, ‘We’d rather bet the farm on Grassley than a bunch of trial lawyers from Texas.’”

‘Squeal’

As Republicans ramped up their criticism of Braley, Ernst, a relatively unknown state senator, was trying to break out of the crowded GOP primary pack and win the chance to challenge the relatively well-known congressman.

Drawing on her farm upbringing, Ernst supporters developed an advertisement that is officially known as “Squeal,” or more commonly as “that castration ad.”

“I grew up castrating hogs on an Iowa farm, so when I get to Washington I’ll know how to cut pork,” she says in the video taken in what appears to be an older hog barn. “Washington’s full of big spenders -- let’s make ‘em squeal.”

The advertisement, which generated national media buzz and almost 600,000 YouTube views, “transformed her candidacy,” according to the Washington Post. Ernst won the primary and has now done what many thought was unthinkable a few months ago: She’s pulled even or ahead of Braley in several polls.

In conversations with political analysts, they noted that, while farmers and ranchers are much smaller in numbers, it’s hard to count them out, especially if they can align with other like-minded groups. In close political Senate matchups, any interest group – be it farmers, ranchers, foodworkers or teachers – could help push a candidate over the top. But efforts have to be coordinated and well-organized.

“If the final outcome is 51 versus 49 percent, a lot of people are going to be able to claim political clout,” adds Guillory.

Kentucky and coal

In Kentucky, Democratic Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes is trying to unseat Mitch McConnell, the U.S. Senate’s ranking minority member. For her, the rural vote in eastern Kentucky may be key, says Jennifer Duffy, senior editor for the Cook Political Report.

However, Duffy says “you have to subdivide your rural voters. Eastern Kentucky is very rural but not very agricultural. It’s coal.” The region is struggling after losing 7,000 jobs directly related to coal mining since 2012.

“And that’s where this race may well be fought. Democrats have always done fairly well in eastern Kentucky. But McConnell has made inroads.”

The importance of Eastern Kentucky voters likely explains why Grimes recently released an advertisement called “Question from David,” which takes a stab at a statement McConnell reportedly made, suggesting that economic development in coal country was not his job. In the ad, Grimes appears with an out-of-work coal miner named David.

For his part, McConnell has criticized Grimes for accepting political donations from anti-coal groups and for not mentioning coal when she appeared at a fundraiser with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev.

In Kentucky, most of the rural vote has turned Republican, but there are still pockets where Democrats are very strong, says Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues and associate professor in the University of Kentucky School of Journalism and Telecommunications.

Cross says this U.S. Senate race may be more about voter motivation and turnout than the issues themselves, especially in a mid-term election when the number of voters traditionally drops.

“In this case, the Democrats are more united behind their Democratic candidate than at any time since her father chaired the state’s Democratic Party and served as a state representative in the late 1980’s,” adds Cross.

Yet, farmers are usually one of the most dependable voting groups, willing to turn out in mid-term elections when many others won’t, says Cross. And farmers are “pretty well lined up behind McConnell.”

Voter turnout regularly drops in midterm elections, according to the Pew Research Center. In 2008, 57.1 percent of the voting-age population cast ballots, lifting up Barack Obama to become the first African American president. In 2010, only 36.9 percent of the eligible voters turned out for the midterm election that put the House back in Republican hands. By 2012, Pew reported that turnout rebounded to 53.7 percent for Obama’s re-election.

In general, the voters who are more reliable in a mid-term electorate are ones that are more Republican, a little bit whiter, and a little bit older than those who turn out for your average presidential election, explains University of Virginia’s Kondik.

“It wasn’t always like that: The ‘Greatest Generation’ came of age during the FDR years and was more Democratic than those who came after them,” adds Kondik. That was about the same time that U.S. farm numbers also peaked.

“But at this particular point in time, the over-65 demographics are generally more Republican and the 18-29 demographic is more Democratic and the older voters come out more regularly in non-presidential elections.”

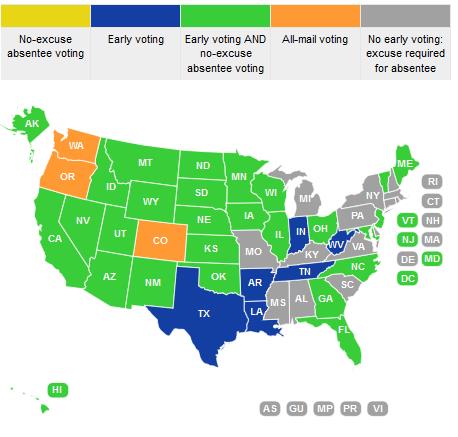

That’s why some Democrats are so focused on get-out-the-vote efforts with younger voters and looking for ways to extend the voting period for more absentee and early voters. According to the National Council of State Legislatures, any qualified voter may cast a ballot in person during a designated period prior to Election Day in 33 states and the District of Columbia. No excuse or justification is required.

Whether or not Grimes will be able to make inroads with farm and rural voters remains to be seen. She’s been invited by the Kentucky Farm Bureau Federation to participate in a candidate’s forum on Aug. 20, where board members can ask questions and media can observe the discussion. McConnell has already accepted an invitation and Grimes is expected to attend. If so, it will be the first time both candidates will face off and respond to the same questions in the same room.

Tribes still matter

The Cook Political Report’s Duffy says the rural vote will continue to matter in places like Kentucky, North Carolina, Iowa, Arkansas, Louisiana, North Carolina and Alaska, where one of Democratic Sen. Mark Begich’s top challengers, former Attorney General Dan Sullivan, is married to a native Alaskan – a member of the Athabascan cultural group.

“The battle is on now for who has the support of the Alaskan tribes. They are not necessarily a monolithic vote, although they can behave that way,” Duffy adds.

Begich already won the support of Sealaska, a regional native institution representing more than 21,600 member-shareholders of the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian tribes. The group endorsed Republican Lisa Murkowski in 2010.

Another prominent native corporation, Artic Slope Regional Corp., endorsed Sullivan, even before he faces off against Joe Miller, who won the last Republican primary for a U.S. Senate seat in Alaska, and Lt. Gov. Mead Treadwell in the Aug. 19 primary.

Face-off over the farm bill

In Arkansas, Sen. Mark Pryor hopes to parlay his support for the new farm bill into a win for his third term. He’s facing GOP Rep. Tom Cotton, the only member of the state’s congressional delegation to vote against the legislation.

“With his vote against the farm bill, Congressman Tom Cotton today cemented his status as an opponent to Arkansas' top industry, which contributes $17 billion to our state's economy and provides one in six jobs here in Arkansas,” noted Pryor on his Facebook page. “The rest of Arkansas' House delegation voted for the bill, which was drafted with the help of Cotton's fellow Arkansas Republicans, Sen. (John) Boozman and Rep. (Rick) mCrawford, and provides disaster aid to our cattle ranchers, makes responsible cuts to spending and gives farmers the certainty they need to succeed.”

Cotton said he primarily voted against the bill because it didn’t do enough to cut and reform the Food Stamp program, but also cited a few other reasons.

“This bill spends too much and leaves Arkansas farmers with too little. Arkansas farmers will receive barely 0.5 percent of its bloated $956 billion price tag — half of what they received in the 2008 bill. Also, it imposes unfair regulations on livestock producers, opening all Arkansas farmers to retaliatory tariffs,” Cotton said in a statement regarding the farm bill conference report.

“This bill can only be called a Food-Stamp bill when nearly 80 percent of its funding doesn’t support farmers. Food-Stamp spending has grown by 86 percent under President Obama and enrollment is at a record high, while 70 percent of adults who receive Food Stamps have been on the program for more than five years,” Cotton continued. “Yet this bill fails to make real reforms — lacking even common-sense work requirements that would provide job training to able-bodied adults receiving Food Stamps.”

But thus far, Cotton’s lack of support for the farm bill doesn’t appear to be hurting him in the polls, given that more of the state has turned Republican red since Pryor was first elected. According to Real Clear Politics, Cotton is leading by almost 3 percentage points in an average of most recent polls. However, the site notes that Pryor’s campaign “is showing some signs of life that weren’t really there a month ago.”

Farmers for Thad

Duffy said that, in general, when farmers are contacted and told the consequences of an election, they vote, but she also noted how the American Soybean Association (ASA) recently used social media to help improve voter turnout in farm country.

She says the Mississippi primary runoff was a good example of farmers reaching out to fellow farmers to help generate more votes for Sen. Thad Cochran in a tough battle against tea-party favorite and state Sen. Chris McDaniel.

McDaniel attracted slightly more votes than Cochran during the initial GOP primary, but not enough to win the race. Three weeks later in the runoff, Cochran beat McDaniel 50.9 percent to 49.1 percent. They were separated by 6,693 votes out of more than 375,000 cast.

“When we started ‘Farmers for Thad’ on Facebook and asked farmers to reach out to their friends and neighbors, we had no idea of how effective it might be,” says Danny Murphy, ASA’s chairman who farms in Mississippi.

The outreach campaign started after Murphy was contacted by the Cochran campaign about the need to boost farmer engagement. Although the Cochran campaign generated a lot of headlines for efforts to turn out black Democrats in the runoff, they also relied heavily on boosting voter turnout among mainstream Republicans.

Murphy turned to Patrick Delaney, ASA’s Washington-based communications director, for help in figuring out how to use social media tools like Facebook to get the word out. He also worked with Elizabeth Jack, wife of Mississippi Soybean Association President Jeremy Jack, to post items on Facebook, but the campaign was not limited to soybean growers. In fact, the site reached farmers of all types and even a few suburbanites.

Delaney says the group posted to the site a whopping 269 times in 14 days. The top post, which reached 15,500 people, was The Clarion-Ledger article in Jackson, which depicted McDaniel’s non-commitment to federal farm subsidies during his stop in the Delta.

The “Farmers for Thad” Facebook page had 570 likes, Delaney says, and more than 200 of them came in the final days of the campaign, “which mean our farmers that liked us really stepped their games up and recruited their contacts as well.”

“Amazingly, we had fewer than 10 negative comments -- from only a small handful of people --throughout the two-week run of the page,” Delaney added.

It was not possible to identify all of the people who may have been contacted through this Facebook campaign, but for those who identified themselves as being in or near a city, Delaney shared a snapshot (below) of the campaign’s social media reach. Cities within the Delta are bolded, he noted, but it’s also worth pointing out several other parts of the state that were involved.

“These are areas in which McDaniel held large leads during the primary, and we were able to cut into that somewhat in the runoff,” explained Delaney.

As a result of this campaign, Murphy said it made him realize how much farmers need to do a better job of reaching out to others.

“I want to continue to remind farmers that they can’t take anything for granted. Each election is very important.

“A lot of farmers just want to do their jobs,” he added. “But we really need to be out there telling our stories and sharing our messages with others.”

#30

Next week: Who are the future faces of rural influence?